Swedish Grace was a design movement in the 1920s that incorporated pared down neoclassicism and … [+]

The “Swedish Grace” movement may not be a household name, but its story is full of design history just like many that are. Around the turn of the 20th century, Art Nouveau came into fashion in arts and design across Europe. The style grew out of the Arts and Crafts movement that sought to reinstall the artist as the progenitor of style and craft, rather than the machine, which was quickly reshaping the industrial new world. As Art Nouveau spread, each country had its own version as their traditional motifs and craftsmanship blended into it.

In the Nordic region, “Romantic Nationalism” or “National Romanticism” was a rediscovery of Nordic history, mythology and esoteric visual references along with some of the qualities of Art Nouveau such as natural motifs and modern materials like glass and iron. In Finland, this new style was used to establish a Finnish identity independent of Sweden and Russia.

In Sweden in the 1920s, National Romanticism had evolved into the little known movement called “Swedish Grace,” which is the subject of an exhibition at Galerie 56 in New York’s Tribeca neighborhood. The work in the show is distinguished by quiet simplicity, colorful geometries and refined neoclassical motifs, marking a shift toward Art Deco, a more geometric and less curvilinear style. Swedish Grace’s pared-down interpretation of National Romanticism and Art Deco was a response to the turmoil in the interwar period of Europe, as Swedish designers wanted to portray a more peaceful, egalitarian version of their country that was not as affected by the World Wars and the political and social upheavals of central Europe.

The carved details of Axel Einar Hjorth’s Caesar console in Zebrano and birch.

In 1925, the Swedish pavilion won the Grand Prix at the International Exhibition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts. Architect Carl Bergsten’s minimalist, neoclassical design for the pavilion featured elongated abstracted ionic columns and was filled with sculptures and furniture by Swedish artists and designers. In 1927, The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York showcased the Swedish designers in an exhibition, “Swedish Contemporary Decorative Arts.” It included a monumental granite-topped cast iron table by Anna Petrus, which is featured in the Galerie 56 exhibition as well. It is the first time it has been displayed publicly since 1930.

Major architectural works include the Stockholm City Hall by Ragnar Östberg and Stockholm Library by Gunnar Asplund. Carl Einar Forseth’s coffee table with Byzantine-inspired mosaics from the city hall is on view at Galerie 56, as are lights designed by Asplund from the library. Other works include wood tables by Axel Einar Hjorth with carved, minimal neoclassical details and Rolf Bolin’s “Sport Urn,” cast in iron with reliefs of Greek-inspired, stylized athletic figures.

The subtle nature of these works highlights the unique position of Sweden’s design legacy in the context of the formative years of Art Nouveau, National Romanticism and Art Deco. While the style is not well-known, it sits within these lineages and has many connections that make it an intriguing moment in design and European history. It is an important moment in the development of the minimalist, craft-based Scandinavian design that is one of the most popular modern styles today. Swedish Grace influenced everything from IKEA to the modern Danish design we associate with “hygge,” the quiet coziness of a warm house.

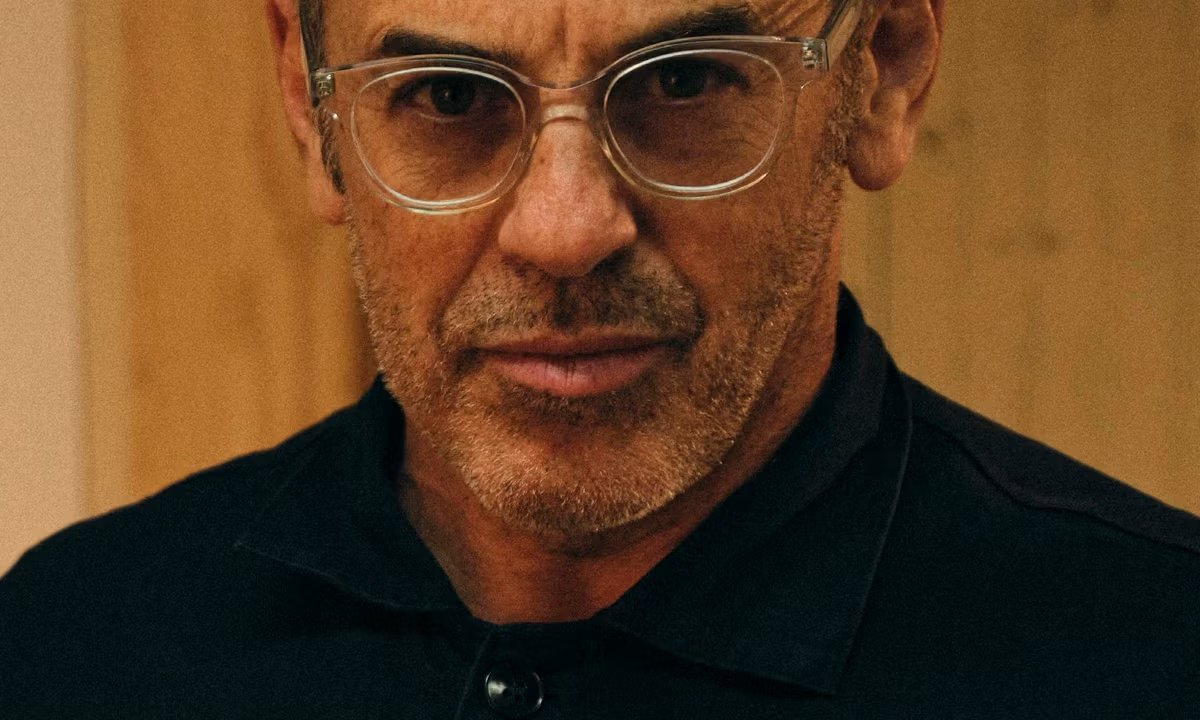

Founded and directed by architect Lee F. Mindel, Galerie56 is located in the ground floor of Pritzker Prize-winning Swiss architects Herzog & de Meuron’s 56 Leonard building, often called the “Jenga tower.” Next month, they will exhibit a show in collaboration with Ralph Pucci, and in March will host a collaborative show around the work of Italian postmodernist designer Etorre Sottsass.

“Swedish Grace” is on view through January 31.

Galerie56 with Anish Kapoor’s bean sculpture at 56 Leonard.