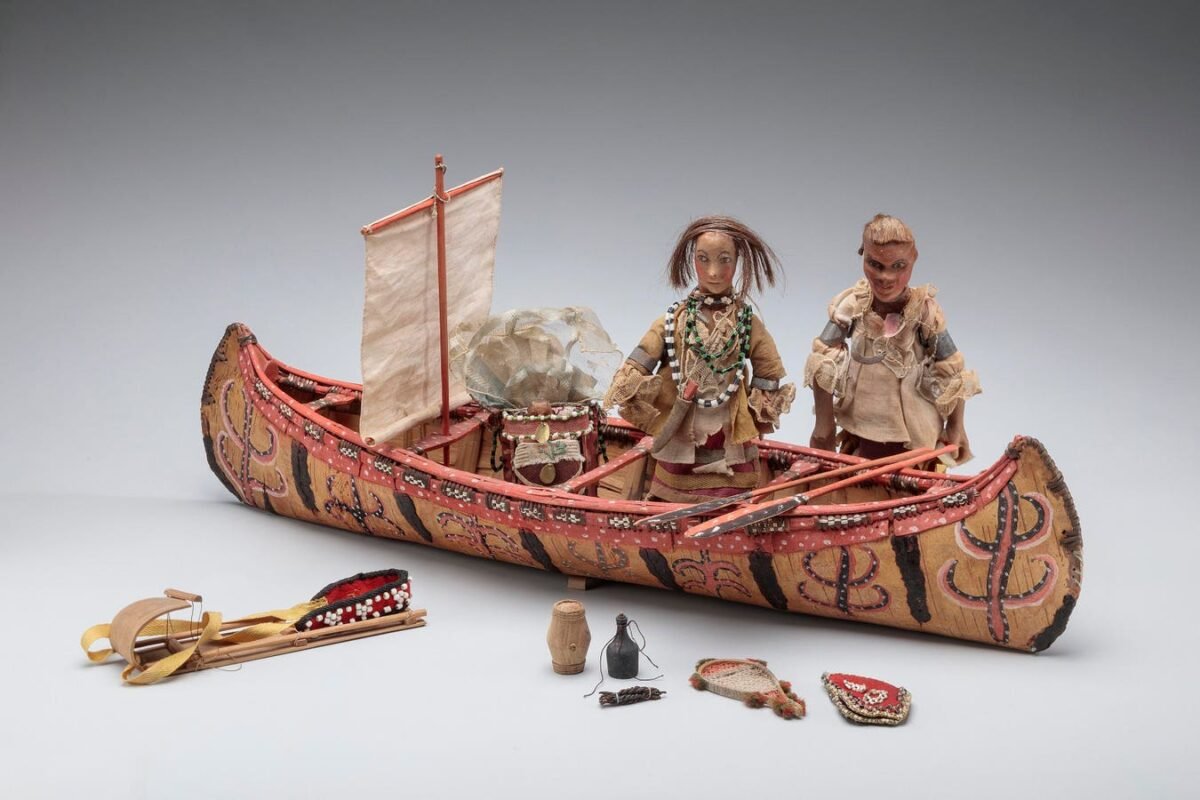

Ancestral Great Lakes Artists, Birchbark Model Canoe and Three Dolls with Assorted Equipment. Birchbark, pigment, hide, wool, cotton, silk, wax, human hair, metal, glass beads, and shell, mid-18th century. Canoe: 26 5/8 × 7 × 5 5/8 in. (67.6 × 17.8 × 14.3 cm). Toledo Museum of Art, Purchased with funds from the Libbey Endowment, Gifts of Edward Drummond Libbey, by exchange, 2023.362, 2023.368a–n, 2023.364, 2023.372

Toledo Museum of Art

European museums and private collections possess a surprising amount of the finest historic Native American artwork ever produced. Same as they do for Asian and African artworks.

When European “discoverers,” traders and military officials began dispersing across the globe in search of colonies and fortune, they picked up souvenirs and items of extraordinary material and aesthetic beauty along the way. In what would become known as North America, before museums were established and before colleges and universities interested in acquiring the material for study were widespread, Indigenous beadwork and buffalo robes and carvings crossed the Atlantic in volume.

One such example is objects originally collected through gift exchanges and purchases during the 18th century by Scottish officer Alexander Farquharson during his military travels through New York and Canada. Farquharson was an officer in the British 42nd Regiment–the Black Watch/Royal Highlanders–raised from loyalist Highland clans in Scotland and sent to North America. The time period coincided with the French and Indian Wars.

For centuries, the items remained in his family estate in Scotland. In 2006, the Farquharson estate decided to downsize. It approached Sotheby’s auction house about auctioning off all the Indigenous items acquired in North America. Thankfully, a private collector in New York who wanted to see collection stay together purchased each item individually at the sale.

The collection was kept in his private home until he passed in 2023. Wanting to fulfill his wishes for the collection to remain intact, the family approached Sotheby’s again about finding an institutional buyer to acquire the lot. One of the potential buyers Sotheby’s approached was the Toledo Museum of Art, located in the historic Eastern Woodlands where the items originated.

Sold.

Now through June 29, the TMA presents “Return to Turtle Island: Indigenous Nation-Building in the Eighteenth Century,” an exhibition showcasing 24 objects initially acquired by Farquharson, later acquired in 2023 by the Museum, on view together for the first time in a public institution. The artworks have returned to Turtle Island, a name given to the North American continent by Anishinaabe, Haudenosaunee, and other Indigenous peoples, referencing the origin story of a landmass built on the back of a great turtle, symbolizing the interconnectedness of land and life.

Robust Trade And Exchange

Leonard D. Harmon, Nanticoke and Lenape, born 1983, Philadelphia, ‘He Walks Around (ayahpamskan),’ 2024. Porcupine quills, horse and deer hide, deer hair, turkey feathers, glass beads, brass beads, brass Ethiopian bells, German wool, and commercial dyes. Purchased with funds from the Libbey Endowment, Gift of Edward Drummond Libbey.

Toledo Museum of Art

First things first. All indications are Farquharson acquired the items ethically. This, of course, was not always the case.

“The strongest evidence supporting that are his letters where he talks about purchasing things that he thinks, in particular Lady Sinclair, Amelia Murray, would find of interest,” Johanna Minich, Toledo Museum of Art consulting curator of Native American art, told Forbes.com.

Murray was the wife of James Farquharson; the couple were patrons of Alexander Farquharson, helping finance his oversees exploits. The exact nature of Alexander Farquharson’s familial relationship with James and Murray has been lost to time.

“There’s a lot written about the Montreal markets and different British, Scottish, French officers purchasing objects that they found beautiful or curious,” Minich continues. “They call them curiosities.”

This was a period during which a craze for collecting unusual and exceptional cultural and natural history items from across the globe and displaying them in private homes swept Europe. The “cabinet of curiosities.”

To ensure the ethical conservation and presentation of the Farquharson objects, TMA collaborated with the Great Lakes Research Alliance at the University of Toronto. Drawing on a network of Indigenous scholars and knowledge keepers, GRASAC provided guidance on the care and contextual display of these significant artworks.

“From all of what we can tell with the market records, which are more or less complete, the people that are buying things in the market are paying really good prices,” Minich said. “It’s not what you see later in the 19th century where a lot of family objects are sold under duress, or, in many cases, literally stolen, or taken out of the ground. This was a period in history where we had this active engagement in the economies on both sides.”

This understanding is critical to the exhibition.

These items were acquired during a period of dynamic interaction between Indigenous and European communities in North America on much more equal terms than would be experienced in the following centuries. The objects represent more than material goods, they serve as symbols of artistic knowledge, cultural exchange, and diplomacy shaping early American history, integral to nation-building and economic sustainability.

“The French are (in North America) trying to court Indigenous people. The British are over trying to court Indigenous people to help them in their colonizing efforts, they’re setting up these political structures, and they’re meeting with Indigenous communities that are themselves taking part in these negotiations,” Minich explained. “These different relationships are being worked out. The relationships of trade, and with trade, you can look at that in a number of different ways. The trade of knowledge, politics, there’s trade of literal monetary exchange.”

Political negotiations were taking place between not just Europeans and Indigenous people, but among different Indigenous communities. As soon as the Europeans arrived, the newcomers immediately recognized they were dealing with well-established political and social structures and set about learning how to negotiate all those different relationships.

Indigenous leaders exchanged gifts and wisdom about the land and animals with their French and English allies during the 16th through 18th centuries. These exchanges had lasting implications for both Native and European communities.

“The modern definition of ambassador or emissary is an individual that goes to another country and represents his or her community by being physically present; these objects serve a similar role. That’s often been dismissed by historians, that the people on (the North American) side didn’t understand how these objects served, but it’s clear that they did,” Minich said. “Both the men who were trading in these objects, but also the women that were making them for trade, understood very clearly that this is an important aspect of being able to convey knowledge of all kinds. Knowledge of their creativity, knowledge of the natural world. They had a keen understanding of how effective these objects were at symbolizing or offering a microcosm of their life to carry that forward to places that they didn’t expect to travel to physically themselves.”

The Leading Role Of Women

Ancestral Great Lakes Artist, Quilled Headband. Hide, birchbark, porcupine quills, natural dyes, and linen thread, mid-18th century. 2 1/2 × 12 1/2 × 3 1/2 in. (6.4 × 31.8 × 8.9 cm). Toledo Museum of Art, Purchased with funds from The Joseph and Kathleen Magliochetti Fund, 2023.375

Toledo Museum of Art

On display are a range of items including quillwork, beadwork, moosehair embroidery, and birchbark artforms, the most remarkable of these being a miniature replica birchbark canoe with three dolls and assorted equipment.

The object was likely produced for market as a souvenir. While not uncommon at the time, due to the organic materials and age, only a handful remain. Of those, the TMA’s is the most complete and in the finest condition.

“We think a lot of these model canoes with the dolls were artistic collaborations between French Canadian nuns and Indigenous women,” Minich said. “We’re still working out who did what parts of it. In this canoe, it’s been suggested that it was likely that the nuns made the wax figures because they already had skill at crafting that type of object. Then the bead work, all of the little delicate beading and clothing for the dolls, was more than likely made by the (Indigenous) women. The canoe itself, it seems likely, was made by a male artist, because the men in the communities would make the full-scale canoes and everything about this model canoe is identical in terms of the structure and the form.”

Primarily centered around the female Indigenous makers, but also with the nuns and the Lady Sinclair, Amelia Murray, “Return to Turtle Island” opens an intriguing window into women’s history. Sources indicate the moosehair embroidery and moccasins sent back by Farquharson especially captivated Murray and her circle. They were prominently displayed.

“I have a feeling that she was expressing an interest in the kinds of objects that Alexander would find because he writes, ‘I will entertain you with anything curious or remarkable that may happen,’ and goes on to say, ‘I’ll try to send back anything I feel that you might find enjoyable,’” Minich said. “I think she has expressed an interest in (these items). Lady Sinclair was ahead of her time in the sense that she was curious about what do these women look like, how do they raise children? What are their thoughts on maternity? Not just the creative arts, but the lives of women in general.”

Atypical to be sure in 18th century aristocratic Europe.

“Amelia Murray, there is evidence that she was this kind of feminist, for want of a better word, not to add a political overtone to it, but she was definitely interested in things that (Indigenous) women were doing, and interested in the possibility that perhaps Europeans didn’t know everything, that maybe Indigenous women did have knowledge that would benefit people overseas.”

Imagine.

Now as then, embracing Indigenous knowledge would serve the world well.