At an art dealership in the Fife town of Methil a middle-aged couple gaze reverently at the collected works on display and finally ask the question that has been nagging at them.

Ryan McPhee has fielded it a lot lately and tells his customers what he knows – that Jack Vettriano was cremated in France shortly after his body was found in his Nice apartment on March 1.

There was no funeral, no memorial service, no fanfare. Those were the painter’s wishes. His ashes are now back in Scotland.

For one of the nation’s best loved artists – a man whose instantly recognisable style adorns the walls of celebrity palaces, bedsits and every size of home in between – it is the most muted of endings.

Memorials to his talent have been conspicuous in their absence too. In Scotland, it is only here at Affordable Arts in the High Street of the town where Vettriano was born that any meaningful tribute to his prodigious output can be seen.

Even Kirkcaldy Galleries a few miles away has not put either of its two Vettriano originals – one donated by the man himself – on display to mark his passing at 73. They remain in storage.

As it was during his turbulent life, so, it seems, it remains after his death: the Scottish art establishment knows better than the self-taught Vettriano what the public want to see.

But what Vettriano knew for certain is how he wanted to make his exit – and the Mail can reveal he left strict instructions.

Celebrated artist Jack Vettriano died at his home in France at the age of 73

A close friend and confidant says: ‘There won’t be a memorial service. Those were his absolute wishes.

‘He had planned maybe ten or 15 years ago for a bigger funeral and then, strangely, when he heard what David Bowie did, which was nothing, absolutely nothing, he said: “That’s what I want to do now.”’

The late rock icon, who died in 2016, avoided the public spectacle of a funeral by opting for a direct cremation with no mourners. He died just two days after the release of his final album, Blackstar, which left a mark on music-lover Vettriano.

‘He really enjoyed that last album that Bowie put out, although he wasn’t a Bowie fan,’ says the friend. ‘Bowie went straight to cremation and Jack decided that was for him.’

It all leaves a curious vacuum around the death of the former miner whose painting career was defined by the competing verdicts of a public who adored it and critics who treated him with devastating disdain.

There is no known cause of death. Little has been revealed of his final years beyond the fact that, holed up in his apartment in Nice, Vettriano had become something of a recluse.

‘He hadn’t painted for a number of years,’ says the friend, who asked not to be named. ‘He had dislocated his shoulder, his right shoulder, and that didn’t help things. He would have liked to have been able to take up his paintbrush again and he tried, but I think he just lost a bit of his creativity with it all.’

The long-term friend, who is still coming to terms with Vettriano’s passing, says it is too early to discuss in detail the circumstances surrounding it.

What is known, however, is he remained scarred to his dying day by the casual brutality with which the art establishment dismissed his life’s work.

Celebrity collectors of it include actor Jack Nicholson, football icon Sir Alex Ferguson, lyricist Sir Tim Rice and the late actor Robbie Coltrane.

Vettriano chose to have his remains cremated without mourners like the late David Bowie

Yet Scottish art historian Duncan Macmillan famously called him a purveyor of ‘dim erotica’ who was ‘welcome to paint as long as no one takes him seriously’.

The Guardian’s art critic Jonathan Jones labelled his paintings ‘emotionally trite and technically drab’ and, in one attack, denied that he was even an artist.

Even after his death The Times’ former chief art critic Rachel Campbell-Johnston suggested the closure of Woolworths, which sold his prints, had dented his popularity.

‘He was at war with the academicians, and both said too much, really,’ reflects the friend now.

‘But I think Jack was quite pragmatic. He knew that, to quote somebody else, he was the people’s painter.’

Yet he clearly brooded on the litany of barbs which dogged his career. He never truly found peace or validation in the simple fact that his work was hugely popular. ‘Who wouldn’t be hurt by some of the things that have been said?’ he asked in an interview in 2022.

‘On a good day, you laugh it off. On a bad day, you go back to that newspaper cutting. I would like somebody, at some point, whether I’m here or not, to have the balls to say: “We’re spending other people’s money, so why don’t we give people what they want?”’

Following his death, another friend, Remi Akande from Edinburgh, told the Sunday Times that, much as he tried to ‘step back to let his paintings do the talking’, the years of criticism ‘had got into his head’.

The 52-year-old said: ‘I remember him saying “It can’t be my work, because it’s sold, so it was obviously a me thing”, and that’s what he couldn’t forget.’ It is also now clear that, latterly, Vettriano was not looking after himself.

There were times when he barely ate, but he smoked and drank and, by his own admission, was on both cocaine and anti-depressants during the coronavirus lockdown.

During the first five months of that period, he found himself the only guest at the Edinburgh Grand hotel in St Andrew Square, having arrived in the capital to discuss an exhibition.

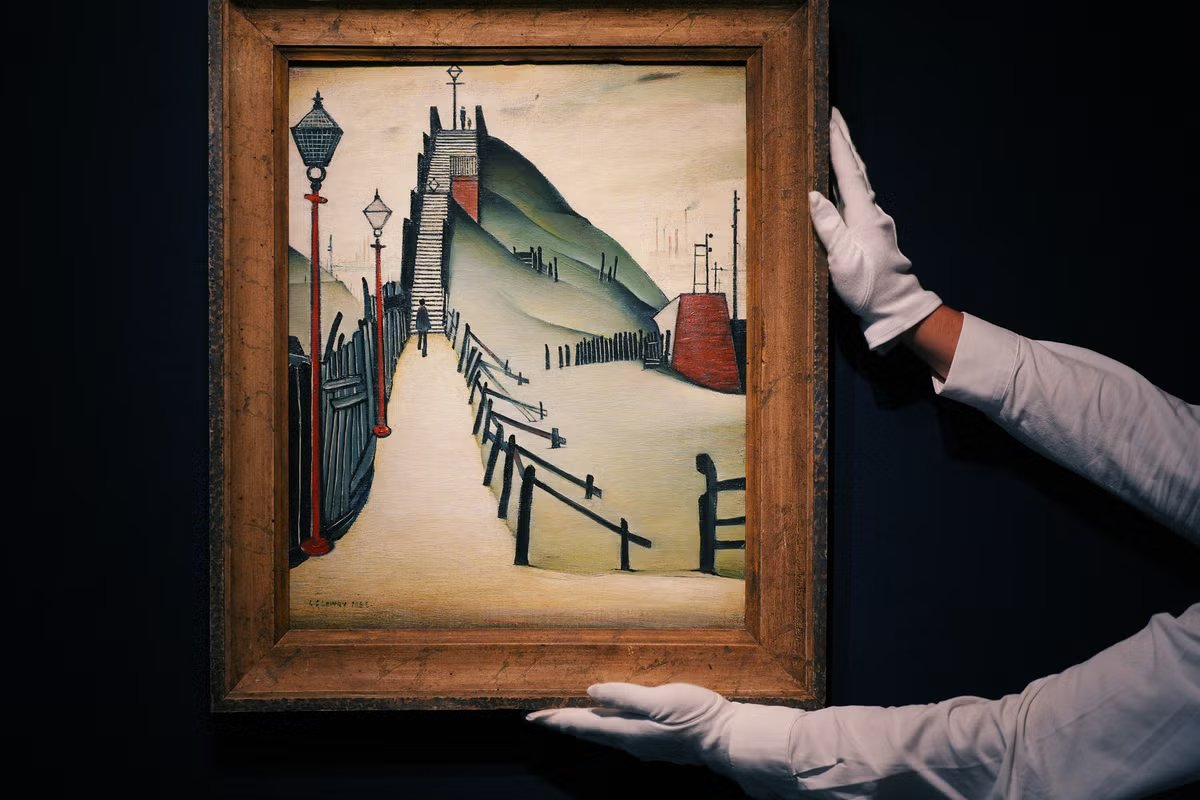

The Singing Butler is arguably Vettriano’s most famous artwork

He was already in a bad way after the breakdown of a ‘disastrous, dysfunctional relationship’. Now, stranded and terrified of catching Covid, he spent month after month alone, watching TV on his hotel bed.

‘I felt like Jack Nicholson in The Shining’ he said. ‘I just used to go to Sainsbury’s, buy a bottle of vodka, and then get some cocaine. I just spent five months watching TV.’

There were numerous health complaints. His dislocated shoulder was still bothering him, years after the initial injury – and, because it was on his ‘painting side’, he suffered muscle cramps when he tried to hold a paintbrush. He had fallen in the snow, damaging his leg and was also battling insomnia.

‘I’ve had to go on a course of strong anti-depressants because I don’t know what’s going to happen to me,’ he told one interviewer forlornly.

‘You don’t have a partner, you’re 69, you’re cut off from your home. I’d like to find a partner. But there’s no hint of that at the moment.’ His words seemed incongruous with the art for which Vettriano made his name. His canvases so often portray confident protagonists, highly versed in the art of seduction. Indeed, the painter regularly modelled the male figure in them on himself.

This was the man who literally re-invented himself in the late 1980s after deciding he was in the wrong life. Jack Hoggan left his dead-end office job, changed his name to Vettriano (a slight misspelling of his mother’s maiden name) and threw himself into the erotic, film noir fantasy world of his paintings.

It spelled the end of his marriage to Gail Cormack but the beginning of a succession of muses. The first was his wife’s best friend, Genevieve, with whom he became romantically involved, and many others followed, among them prostitutes from Edinburgh sauna houses where he could drink in the atmosphere of illicit sex.

He made history in 2004 when The Singing Butler – a 1992 painting – sold at auction for £744,800, breaking all records for a Scottish painting at the time.

His fortune, which largely came from reproductions, allowed him to buy homes in London and Nice. And, for all that the art establishment’s reviews were brutal, his name continued to fill galleries.

In 2013, Glasgow’s Kelvingrove Art Gallery put on a retrospective of his work, featuring more than 100 of his paintings.

It became the most successful exhibition in its history, attracting 132,500 paying visitors.

He was featured in several TV specials, including one in which he produced a painting of Billy Connolly for his 75th birthday. It was recreated as a huge mural on the gable wall of a block of tenement flats in Glasgow.

And yet, for all his fame and success, the pursuit of muses and potential partners – and his fear that his age and health presented ever bigger impediments in that – was a recurring theme.

‘I must get somebody before I get infirm. I must,’ he said in 2009.

‘As you get older you need a partner. That’s what I would like,’ he admitted in 2021.

And then, the following year: ‘I’ve got a muse, a beautiful woman in Nice where I have an apartment. And I think I’ve found a new one in Edinburgh.’

He added: ‘I can’t go on dating sites. I can’t go clubbing. I can hardly bloody walk, never mind dance. So the opportunities to meet the opposite sex are really dwindling.’ That was the year of his final exhibition – in his former hometown of Kirkcaldy – which showcased many early works completed when he was still Jack Hoggan.

Despoite his success, Vettriano was at times dismissed by the art establishment

He said at the time, portentously as it turns out: ‘I’m not trying to be the harbinger of doom, but I think this might be my last exhibition in Kirkcaldy, so it’s a kind of sentimental journey.’

At the same gallery today, an exhibition of photographs captures the history of the local mining industry, of which Vettriano was briefly part.

But there is no evidence of his art in the town where the painter was based for many years. A staff member says it may be looked out later in the year as part of the venue’s centenary celebrations.

Commenting on its absence, Vettriano’s friend tells the Mail: ‘I find it extraordinary, given that his last exhibition was in Kirkcaldy. I don’t know what they’re playing at and I’m not happy about it.’

Back in Methil, a book of remembrance is laid out at Affordable Arts for visitors to leave their final thoughts on the man. There are tributes from visitors from Spain, Germany and Canada – and others from much closer to home.

‘At school you pinched the ribbons from my hair and your mum asked you to put them in your long hair for school,’ says one. ‘Love always for the memories of growing up.’

‘Your art captured mystery, romance and intrigue,’ says another. ‘Thank you for sharing your talent with the world.’

A third reads: ‘So glad to have met and chatted with you at Fife College and very grateful to win the scholarship you offered.’

Mr McPhee, whose father Duncan was Vettriano’s picture framer in his early days, says around 500 people a week have been coming to see the exhibition, which includes several Hoggan originals as well as two Vettrianos.

Normally the gallery owner’s weekly clientele is a quarter of that number.

He adds: ‘A lot of the people are saying there’s nothing else in the local area – or afar. I’ve had customers come in to say they went to the Kirkcaldy gallery to see if there was a book of condolence or anything there and there’s nothing.’ Business is also brisk at Palazzo 1!, in Bologna, which is hosting the first Italian exhibition of Vettriano’s work.

The painter was found dead less than a week after it opened.

Its tribute to him on hearing the dreadful news was more poignant than any to emerge from the art establishment in Scotland.

‘He was not only an extraordinary artist,’ wrote the venue management, ‘but also a deeply private and humble man who was infinitely grateful for the support and admiration of those who loved his work.

‘His paintings, capturing moments of intrigue, romance, and nostalgia, have touched the hearts of so many around the world, and his legacy will continue to live through them. We want to remember you this way: approachable, ironic, and kind.’

Vettriano certainly was all those things and others besides. Flawed, fragile – perhaps even self-destructive.

On the evidence thus far in his native Scotland, the critical acclaim he craved in life is no less elusive in death. But he died knowing that his work spoke to countless people across the world and hangs on their walls still.

Critics speak for themselves.