Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

In a corner of the basement at London’s Warburg Institute, there are more than 30,000 images bound into red and blue volumes. The Image of the Black archive is an ambitious collection of photographs of artworks, compiled between 1960 and the 1990s by the Franco-American art collectors and philanthropists Jean and Dominique de Menil. Created as a response to the civil rights movement in the US, the images together document the representation of Black bodies in western art over nearly 5,000 years. There are two iterations of the collection, one housed at Harvard, and another at the Warburg.

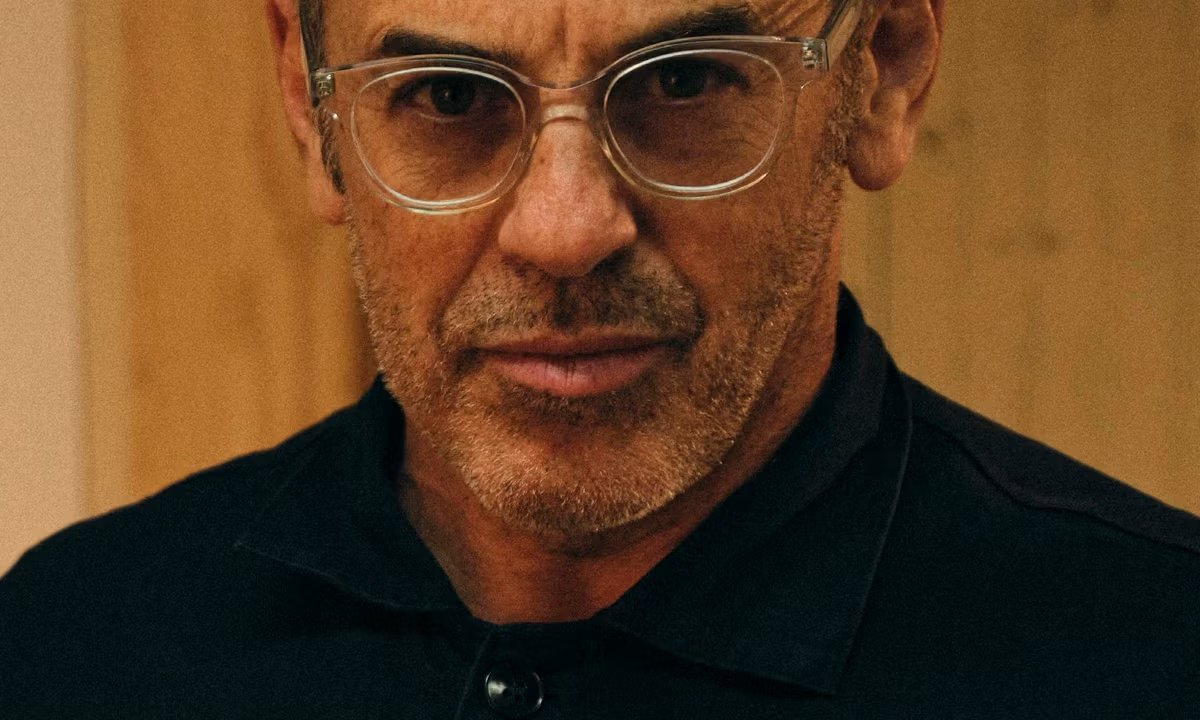

The British multidisciplinary artist Edward George says he spent two months of his 12-month residency at the Warburg simply flicking through each image. Without pausing to question why some stood out more than others, he saved the ones that caught his attention to review later. “If an image leapt out and went, ‘you haven’t seen me before, you don’t know what the hell I am,’ it was in,” he says.

This left him with about 15,000 images of artworks, ranging from paintings by Hieronymus Bosch to Degas’s depictions of the mixed-race circus performer Miss La La to a mass of unknown and undated pieces. Over the rest of the year, George would whittle those images down to roughly 400; these now make up “Black Atlas”, an hour-long video piece and three collage triptychs.

George, 62, has taken inspiration from the “Bilderatlas Mnemosyne”, a project begun by art historian and Warburg Library founder Aby Warburg in 1927. These are large black panels that Warburg collaged with images from a range of sources — everything from details from Renaissance paintings to pictures of Greek statuary to newspaper clippings — hoping to map out recurring visual themes across history. The project was still a work in progress when he died in 1929. “He had this idea that you could find in repetition of small objects some kind of new knowledge about time and the world and space,” George says. “You do wonder what the repetition of images of race might tell you about race and how race works.”

After choosing his pictures for “Black Atlas”, George thought about the various themes that tied his choices together. “What I found was the prevalence of the oddest of things,” he explains. He singles out dogs, for example. “I didn’t go looking for dogs. The dogs found me.” His approach was associative. Under this category he includes literal images of dogs, but also a man cracking a whip or a naked woman’s back. “My question was about what happens when you arrange them all together,” he says.

In the video piece, images follow each other in slow succession, creating links between the ones that came before and after. “One of the things I’ve discovered in this is that some images resist new meanings historically,” he says, noting another section on sex. “The Black male body and the Black female body are always constituted as something to do with sex.”

George refuses simply to accept the photographs in the Image of the Black archive as depictions of Black people, without questioning the circumstances of their creation. “They’re images by white people of Black people,” he says. “So, when you see a Black person [in these artworks], you’re not looking at a Black person, you’re looking at an idea of a Black person by a white person, which is really more to do with whiteness than Blackness.”

In his video narration, George addresses the lack of context of many of the artworks, noting that some Black figures may have been entirely constructed from an artist’s imagination. “I’m not sure who among the images is a ‘ghost’ and who may have been among the living,” he says in the audio. In person, he explains, there is power in the moments when context is given or withheld. “There is a context for thinking on racism. Without that context, those discussions can’t take place.”

George believes that the de Menils intended to give a “forceful wake-up call” to racist white Americans through their collection. They hoped to offer an idea that “the objects of your hatred — the Negro, the person of colour, the African American — are actually a part of the history of what you call beauty,” he says. Given that Black people are ever-present in western art, even if they appear in the background or a corner, the collection poses the question: “How can you hate something that’s a part of your perception of beauty?” Yet for all that idealistic underpinning, George says, “You do get beauty, but it’s inseparable from a history of violence.”

At a time when diversity, equity and inclusion programmes have been dubbed “immoral” by the White House and banned from public institutions in the US, the questions the archive posed at the time it was made have come back around. “The idea is that [an archive such as this one] shouldn’t be a part of the present,” George says, pointing out that history has repeated itself. “The very necessity that kick-started its existence in the ’60s is no less present in 2025.”

October 10 to January 17, warburg.sas.ac.uk

Find out about our latest stories first — follow FT Weekend on Instagram, Bluesky and X, and sign up to receive the FT Weekend newsletter every Saturday morning