‘Nji-sa ndoweminaanik/To Our Sisters,’ Yvonne Walker Keshick (Little Traverse Bay Bands of Odawa Indians) Harbor Springs, Michigan. Michigan State Gchi-kinoomaagegamik, Michigan Naadiziiwin gegoo Zhichigan nokiiwin/Michigan State University Museum, Michigan Traditional Arts Program Collection 7594.20.

Minnie Wabanimkee

Before beads, there were quills.

Before beadwork, quillwork.

Long before European colonial settlers introduced the trade in glass beads to North America, porcupine quills were the medium Native artists across the continent used to adorn baskets and clothing with decorative designs. Using porcupine quills for artistic purposes exists nowhere else on Earth and represents one of the earliest forms of decorative art in North America.

Native artists of the Great Lakes region specialize in using quills, sweetgrass and birch bark to create brilliant, embroidered quill boxes and art featuring designs inspired by woodland floral and fauna, including vibrant geometric designs. Their contemporary creations are featured in an exhibition, “Gaawii Eta-Go Aawizinoo Gaawiye Mkakoons: It’s Not Just A Quillbox,” on view at the Eiteljorg Museum of American Indians and Western Art in Indianapolis through March 29, 2026. The presentation originated at the Ziibiwing Center for Anishinaabe Culture and Lifeways in Mt. Pleasant, MI.

Porcupine Quill Art

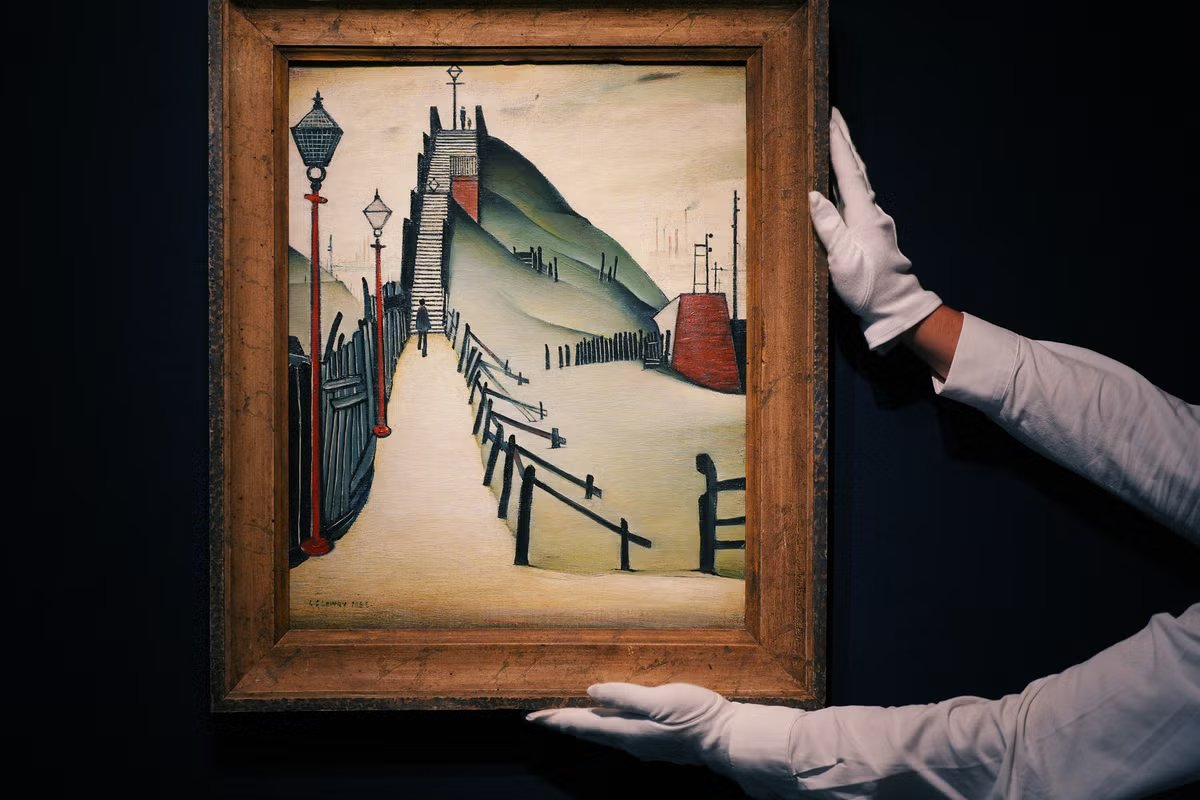

“Gaawii Eta-Go Aawizinoo Gaawiye Mkakoons: It’s Not Just A Quillbox” exhibition installation view at the Eiteljorg Museum of American Indians and Western Art in Indianapolis. The exhibition is open daily through March 29.

Eiteljorg Museum

“How in the world?”

Porcupine quill art boggles the mind. How do these artists take that material and create those amazing objects?

Obviously, the process begins with porcupines. Porcupines give their lives to the making. They are either trapped and killed or gathered as roadkill nowadays. Indigenous people often honor animals killed for food, thanking them for their life-giving sacrifice, and in a similar way with the porcupines, artists attempt to honor the animal through their finished work.

Quill artists in the Upper Midwest typically source porcupines between the first fall frost and first snowfall or in early spring after the snow melts; porcupine quills contain oil, and quills acquired in summer are full of this oil and turn yellow when dried.

An average adult porcupine may contain 40,000 quills, but porcupines are not prickly to touch like a cactus, they’re hairy. Long guard hairs cover the animal. These guard hairs must be removed before accessing the quills. Porcupine guard hairs are used in another astonishing Native cultural expression: hair roach head dresses.

Porcupines are cleaned by pulling out the guard hairs and shorter under hair, then by removing the quills in sections. The video below shows Monica Jo Raphael (Anishinaabe / Sičáŋğu Lakota), Hoback curator of Great Lakes Native art, cultures and community engagement at the Eiteljorg Museum, cleaning a porcupine. She is a fifth-generation quillwork artist with two pieces in the show she helped bring to the Museum.

Different areas of the porcupine have different sized quills. Raphael prefers using quills from the animal’s sides. She uses colanders to sort the quills into like sizes. When making quill art, the lengths of the quills can vary, but the width needs to be consistent.

Separated quills are washed in liquid soap with a small amount of bleach. They are then rinsed, dried, and stored them.

When Raphael is ready to start making art, she’ll wash the quills again before dying them. Coloring can be achieved using commercial products or organic materials like berries, cherries, dye from the cochineal beetle, or even Kool-Aid and Easter egg dye, both of which Raphael has used to produce particularly vivid, wild colors.

In quill art, think of quills as the paint and birch bark as the canvas.

Quill artists in the Great Lakes region gather bark during a two-week period in late June or early July when the material is moist. That’s what they’re looking for. Bark is washed and then dried in the sun. Trees of different sizes and ages have different color bark. Bark color can also be manipulated by drying time–the longer it’s in the sun, the darker it gets.

Quills are embroidered into birchbark with small sewing awls made from needles. The bark is pierced by the needle and the quill is pulled through with tweezer.

Quills are used one at a time to create a variety of fantastically intricate shapes and designs. Designs are drawn on the bark and etched in with needles before embroidery begins.

Among the Anishinaabe, quillwork pieces are often finished off with braided sweetgrass trim.

Contact with Europeans brought glass beads–trade beads–in the 16th and 17th centuries depending on where a tribe was located. Beads are much easier to use, eliminating the great deal of preparation required in quillwork. By the mid-1800s, trade beads were readily available across the continent and had largely replaced porcupine quills. Not entirely. Never entirely.

As part of the exhibition, the Eiteljorg will present quillbox programs, including live demos, a talk and workshop, all featuring artist Melissa Peter-Paul (Mi’kmaw) on February 26, 27 and 28. Visit www.Eiteljorg.org/events for details and registration.

Quillboxes

“Gaawii Eta-Go Aawizinoo Gaawiye Mkakoons: It’s Not Just A Quillbox” exhibition installation view at the Eiteljorg Museum of American Indians and Western Art in Indianapolis. The exhibition is open daily through March 29.

Eiteljorg Museum

Birch bark quillboxes emerged among Native people as containers. They also produced larger storage vessels, like buckets, also from birch bark. Like the quillboxes, these containers were similarly adorned with quill art. Buckets for strawberries would feature strawberry designs on the outside. Buckets for maple sugar, maple leaves.

“Whatever birch bark will hold, it will protect,” Raphael told Forbes.com during a Zoom interview, passing on an oft-repeated Anishinaabe mantra.

The Eiteljorg exhibition focuses on how quillboxes are made and their importance to the Anishinaabe peoples. Not only pre-contact, but in the 20th century as well, when they took on a completely different and separate purpose for the Grand Traverse Band of Ottawa and Chippewa Indians, of which Raphael is an enrolled member. The tribe calls the northern and western portions of Michigan’s lower peninsula home.

“In those areas, they had a Works Progress Administration project where they had (Native people) making these quillboxes,” Raphael explained. “(Quillboxes) were used for commerce. Northwestern lower Michigan historically has been a tourist (destination). Wealthy people from southeastern Michigan, like the Fords, they all had summer homes up there and they would buy quillboxes.”

Raphael’s grandmother participated in the WPA quillboxes-as-souvenir collectables project.

Contemporary quillwork artists across the continent are taking the medium into dynamic, new directions, incorporating quillwork into paintings, textiles, jewelry, and beadwork. They’re mixing mediums. Diversifying it uses. Contemporizing quillwork. Experimenting with brighter, unnatural colors.

Always grounded in tradition, however. For the Anishinaabe, a major component of that tradition is Anishinabemowin, the spoken language of the Odawa (Ottawa), Ojibwe (Chippewa) and Bodewadmi (Potawatomi), all Anishinaabek peoples of the Great Lakes region. “It’s Not Just a Quillbox” has bilingual panels printed in Anishinabemowin, followed by English translations.