In 1976, the artist known as Colette revolutionized performance art in the dreamiest way possible: at the Clocktower Gallery, a seminal art space in a regal Beaux-Arts building in Lower Manhattan, she curled up and went to sleep.

Entitled Real Dream, this slumbering performance was the centerpiece of “Colette: Room Environment Installation,” an exhibition curated by Alanna Heiss, the innovative founder of P.S.1 (now MoMA P.S. 1) and one of the most esteemed curators of the 1970s.

Colette’s performance became the stuff of legend for an enclave of the art world—long before Tilda Swinton dozed in a glass box at the Museum of Modern Art, or critics went wild for the drowsy protagonist of My Year of Rest and Relaxation, or the rise of sleep as protest art. Colette had touched on the creative potential of dreaming, of plumbing an utterly rich world of unreality, with the single artist orchestrating it to perfection. “I’ve always had a vision, from the beginning. Literally visions—and I didn’t take drugs,” Colette told me during a recent conversation about what spurred such a creation.

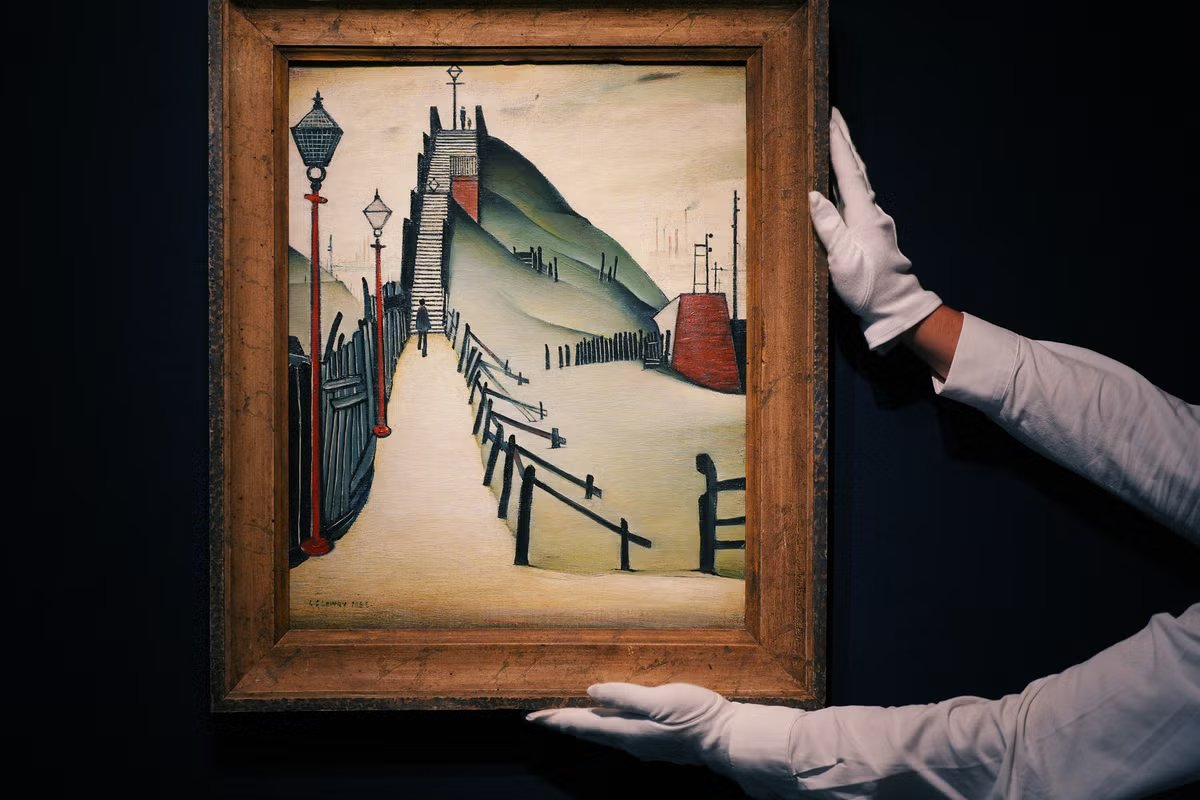

Colette in TIP Magazine, Berlin, circa March 1984

This encompassing, sweeping, world-building impulse has underlined Colette’s career for over 50 years and has kept a certain sect of art lovers enraptured.

“Colette, for those who do know her, is an icon. From people who know her from the ‘70s to this newer young generation who have found her work, she has such a diverse range of people who are aware of her,” said Sacho Lo of Company Gallery. Company is currently presenting “Colette Lumiere: Everything She Touches Turns to Gold,” an exhibition centered around paintings the artist created during the 1970s and ‘80s (through March 1). “She was somebody who was ahead of her time and created a way to be an artist where you don’t need to fit into a box,” Lo added.

Installation view of “Notes on Baroque Living: Colette and Her Living Environment, 1972–1983,” 2021. Photo courtesy of Company, New York

Colette, who is now known by the persona Colette Lumiere, has occupied an ever-changing set of guises over the decades. The first shift came in in 1978, at the Whitney Museum of American Art, when she staged Colette’s death, by the prick of a staple gun, her preferred tool. The artist emerged several days later at P.S.1 with a new name: Justine, president of Colette is Dead, Co, and the frontwoman of a band the Victorian Punks.

Over the years, she would become Mata Hari and the Stolen Potatoes, Countess Reichenbach, Olympia, Colette de la Victoire, and Colette Lumiere, among others. Channeling the mystique of fairytales like Sleeping Beauty, she mined a world of femininity, centering her own body as an evolving muse (sometimes she appeared nude, to the chagrin of some feminist artists, she said).

Installation view “Colette Lumiere: Everything She Touched Turns To Gold” 2025. Courtesy of Company Gallery.

Despite her pioneering impact, many in the art world are surprisingly unfamiliar with her name, though a burgeoning resurgence of interest in her work has been percolating over the past decade.

In 2013, Bomb published an interview with Colette Lumiere by the writer Katie Peyton Hofstadter, which introduced a new generation (including me) to her work. Then in 2020, wider awareness of her oeuvre emerged when a Kickstarter campaign launched to save her Living Environment, an immersive, evolving installation she installed in her Pearl Street apartment between 1972 and 1983, which had fallen into disrepair after years in storage (the work, made largely of ruched parachute material, had nearly been acquired by Stockholm’s Museum of Modern Art, via dealer Leo Castelli, but the deal fell through).

Colette Lumiere, Recently Discovered Ruins of a Dream (1973-2023). Courtesy of the artist and Company Gallery.

This interest reached a new peak in 2023, when Company, which now represents Colette, staged its first solo exhibition of her work “Notes on Baroque Living: Colette and Her Living Environment, 1972–1983,” bringing together elements of the Living Environment, including mixed-media paintings, sculptures, light boxes, costumes, short films, music, performance documentation, and ephemera.

That same year, Company presented a restaging of one of Colette’s sleeping works—this time with a synthetic sculpture of the artist—to acclaim at Art Basel. Now, Company’s second exhibition of her work delves into Colette’s Berlin era of the 1980s, when she worked under the pseudonym Mata Hari and the Stolen Potatoes.

So, who is Colette and why is her work important?

Colette’s New York Origins

Born in Tunisia, in 1952, and raised in part in France, Colette came to New York in 1970. Her first works were large-scale anonymous paintings on the streets of SoHo. “I was compelled to do these street paintings very spontaneously, intuitively. I felt I needed to do this,” she said of that era.

By 1972 she had commenced a series of pivotal installations in storefront windows called “inner sculptures.” Her first was a tableaux vivant recreating Eugene Delacroix’s Liberty Leading the People (1848), with Colette as the central figure.

Courtesy of the artist and Company.

“My art history started with French art history. One of the first works I did was Liberty Leading the People,” she recalled “I did it very innocently. I was very young. Liberty’s breast is out and she doesn’t give a shit. She’s leading the men and she’s so strong. I made the work with nothing, some towels and red, white, and blue fabric for the flag.”

During these years, Colette found herself straddling a world of artists, including conceptual artists, who didn’t quite understand her ethos or aesthetic, which was decidedly feminine and often involved her own partially nude body. In 1976, she installed her work As Marat in David’s Wrath at P.S.1 with Colette posing as the French Revolutionary martyr as immortalized in the famous painting Death of Marat by Jacques-Louis David.

“I thought of that as a feminist piece because it was a time of high feminism, but many artists didn’t like me because I didn’t look like I was tough, though I was in my own way,” she recalled. “To me, feminism was just being a woman and being natural about it, not being apologetic. I always felt that was a big contradiction in early feminism. It was harder for women, though, and I have a lot of respect for the women before me.”

Ultimately she found kinship with a group of artists including Jeff Koons and Richard Prince. Her 1979 film Justine & the Boys included both Koons and Prince, among others, and was shot by Robert Polidori in her Living Environment. Her forays remained deeply experimental, at times delving into fashion, collaborating with Fiorucci; or music, as in her limited-edition LP, Beautiful Dreamer from 1978.

A magazine page featuring Colette in an article from NY Talk, 1986.

“People see a big difference between the photo works and the painting, but for me, it’s all the same. It’s all me. It is all one vision. We’re all one, and I’m all one—that kind of thing,” she said. “I love to experiment and I feel I have something different to say or I feel restless and then a persona appears, or destiny, or life, brings me somewhere else just when I think I’m very cozy and I’ll stay right here. Boom!”

Though discourse around Colette’s works has often centered on her performances and installations, painting has provided the backbone to her practice, with a nearly daily practice of “metaphysical portraits.” The exhibition at Company foregrounds this practice, with a gallery devoted to large-scale mixed-media paintings in soft hues of pinks, whites, and golds.

A Punk Performing Femininity

Colette has often occupied the center of her works as an artwork to be viewed, and as a performer and director, often leading to some confusion. “From the beginning, Colette has adopted starring roles, for which she creates sets that blur distinctions—not just between artist and character but also between the character’s stage and our shared environment,” wrote art historian David J. Getsy in an important essay on her work.

Colette Lumiere, 2023. Photo: Tonje Thilesen.

Her works often defied the visual languages of her era. At the height of Pop art and later Minimalism, she cultivated a luxurious eroticism cast in pales pinks and satins, which drew equally from the opulence of Rococo and the rebellion of punk. Her guises have emerged from a long history of heroines, often recasting these figures in her own mythology, creating a space where life and performance, dream and reality mix together. Art history has always been close at hand. While working under the guise of Olympia, for instance, she created a series of “colettesized” artworks inspired by 18th-century masterpieces from Fragonard, Boucher, and Watteau.

“Everything She Touches Turns to Gold,” for its part, spotlights works made in the 1980s in Berlin, a period when Colette embodied the persona of Mata Hari and the Stolen Potatoes. Mata Hari, as a guise, hinted back to the real-life performer accused of espionage, as well as the likes of vampy icons including Theda Bara and Marlene Dietrich.

Colette in TIP Magazine, Berlin, circa March 1984

During her Berlin era, Colette worked in a theatrical language inextricably tied to nightlife. At the city’s famed Fofi’s Nightclub, she filled a gold-draped Volkswagen with “golden potatoes.” The golden potatoes, seemingly plucked from a fairytale, served as a potent, alchemical motif, in which she transformed the everyday into the alluring.

Often, these performances and static artworks evolved into larger collaborative projects. Much like Justine and the Victorian Punks, which debuted in 1978 in New York, Mata Hari eventually became a visual art band that made its debut at New York’s Danceteria, where she hosted numerous interventions. Colette’s encompassing, multifaceted approach to art-making has made her work difficult to categorize, and even harder to preserve and archive.

Installation view “Colette Lumiere: Everything She Touches Turns To Gold,” 2025. Courtesy of Company.

“Being an artist, a woman artist in the ’70s and ’80s, women were underrepresented in this male-dominated field,” said Lo, “But truthfully, I think she’s been overlooked because of how fluidly her work has never been categorized as something. It harder to fit her into a single art-historical narrative.”

Over the years, many of Colette’s large-scale works wound up in storage and some suffered damage as a result of Hurricane Sandy. In securing her legacy, the gallery is currently restoring some of her works. “For her to trust us with her work, especially as somebody who literally embodies her art, we are very appreciative,” said Lo. “These works are her like children.”

Artistic Rebirths

A series of black-and-white portraits entitled “The Silk to Marble Series” anchors one wall of the Company exhibition. In these large-scale works, Colette appears veiled in a white sheet that gives her the guise of a classical marble sculpture. The works were her own way of reimagining herself before she moved to Berlin (these were shown at Künstlerhaus Bethanien in 1985). Though in a different visual vernacular, her works align her as a peer to Cindy Sherman who created her iconic “Film Stills” from 1977 to 1980.

Installation view “Colette Lumiere: Everything She Touches Turns To Gold” 2025. Courtesy of Company.

But Colette’s works have always expanded beyond the confines of the discrete art object and into the lived world. This encompassing approach has drawn a new generation of artists to Colette, as a visionary who predicted our current art moment.

“She builds worlds out of strangeness and softness. She plays with femininity from a sophisticated, nuanced, and honest perspective that doesn’t always align with an older feminist orthodoxy. I wield pink silk, tulle dresses, and girlish imagery, my rage tied up in a ribbon bow, to reject the devaluation of a particular expression of femininity. When I saw Colette’s work, I realized I was tapping into something bigger,” said rising artist Morgane Richer La Flèche, who recently exhibited her delightfully explosive paintings in the exhibition “The Cat Wife” at New York’s Salon 21.

Richer La Flèche sees an artistic predecessor in Colette beyond her work alone. “She uses photography to build personas in a way that is so contemporary. The fluidity between her artistic process, her fashion, and her storytelling merges documentation and performance. Colette helped create the language that artists who grew up on Instagram are fluent in. She’s an original, and I think her refusal to bend to a boring definition of the serious artist makes her appeal to an irreverent generation,” she added.

Boring she most certainly is not, and the artist, who is back in New York working, is currently putting her finishing touches on a film that will likely premiere later this year. Amid this renewed interest, Colette’s world, again, seems to be brimming with new possibilities.

“Colette is ever-evolving, always transforming.” Lo said, “She’s an artist that really uses the self-methodology of not only creating art but living it.”

“Colette Lumiere: Everything She Touches Turns to Gold” is on view at Company through March 1. The gallery will host a closing reception for the exhibition on March 1, 5–7 p.m. with the artist present.