ST. PETERSBURG — The life-sized figure looks hot and weary, carrying a jug of water and a heavy backpack. There’s a human skull on the ground, a memento mori. But above his head are a flight of monarch butterflies, a symbol of hope and a play for compassion for the people who risk their lives in pursuit for a better one.

Antonio Castro’s charcoal, pastel and pencil artwork “Emigrante (Ni Criminales Ni Rateros/Immigrant)” is a stunning introduction to “Icons & Symbols of the Borderland: Art from the U.S.-Mexico Crossroads,” the new exhibition at The James Museum of Western and Wildlife Art.

Continuing the museum’s effort to show expanded perspectives of the American West, this show presents the work of Indigenous, Mexican and American people who live in the region near the U.S.-Mexico border.

The robust exhibit showcases nearly 80 pieces of artwork from 27 artists who are members of the JUNTOS Art Association, established in El Paso, Texas. Media ranges from paintings and sculpture to neon and paper, with subjects ranging from whimsical to poignant.

It was curated by artist Diana Molina, with its first showing in 2015 at the University of Texas at El Paso’s Centennial Museum. It has been traveling ever since throughout Texas and it will keep traveling after it closes at The James Museum. Associate curator Caitlin Pendola brought the exhibition to the museum.

It has four themes: Environment, Borders, Sacred and Profane, and Foodways. Molina said she drew inspiration from Mexican bingo cards called loteria that feature illustrations with text, like “la corona” with a crown. Thinking about those symbols was a way to organize the artwork.

Another overarching theme is movement, and the notion that the world would be a mundane place if people didn’t migrate. It also highlights the intersections of the cultures of people who live near the border, while emphasizing humanity.

“This border story speaks of that mestizaje (of mixed race),” Molina, who is Mexican and caucasian, said. “I say ‘soy mestiza, I’m a mix.’ So many of us are. And ultimately, this human experience has so many roots and branches.”

Molina’s collages made from recycled paper, like labels from Dos Equis beer bottles that look like serape blankets, are included. So is her photography, like “Piedad,” a photo of a sandaled foot belonging to a rarámuri, or foot-runner member of the Tarahumara of Northern Chihuahua, Mexico, said to be the best long-distance runners in the world.

Another artist in the show, César Martinez, was a prominent figure in the Chicano art movement of the 1970s, Pendola said. He is also Molina’s life partner and works in a variety of media. His digital print, “Mona Lupe: The Epitome of Chicano Art,” places the face of the Mona Lisa in the pose of Guadalupe, the Virgin Mary, whose image appears frequently throughout the show.

Explore Tampa Bay’s sights and bites

Subscribe to our free Do & Dine newsletter

We’ll serve up the best things to do and the latest restaurant news every Thursday.

You’re all signed up!

Want more of our free, weekly newsletters in your inbox? Let’s get started.

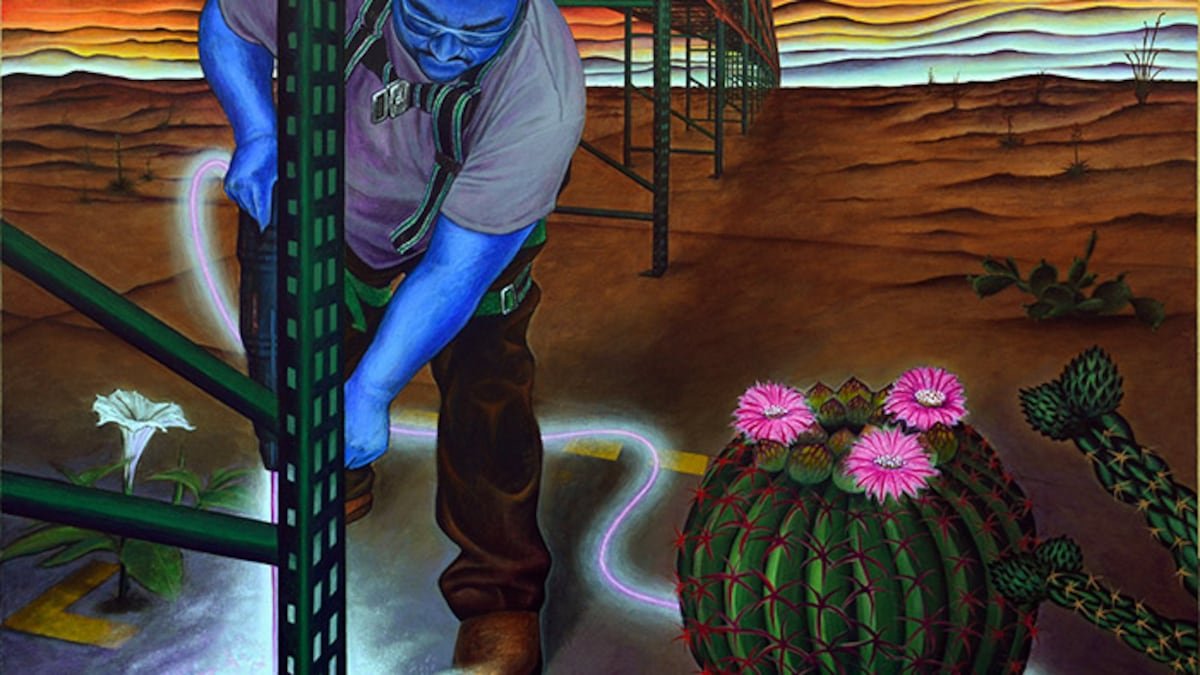

Oscar Moya’s painting “Borderline” is reflective of his experience of emigrating from Mexico City to the U.S. at 15 and working as a migrant worker from San Antonio, Texas, to Chicago, Illinois. The painting depicts a co-worker repairing a warehouse racking system to store goods made in Mexico and assembled in the United States.

The title, “Tlazolteotl as a Horse,” may be a tongue-twister, but Richard Armendariz is clear about the meaning of his powerful carved and painted wood panel. It’s inspired by the Mesoamerican deity Tlazolteotl, the goddess of midwives who ingests disease so a child will be born healthy. “In my painting I depict a horse as the midwife deity ingesting drones and missiles on a dystopian future border,” he states on the work’s label.

Mark Clark’s “Saludos Desde el Otro Lado (Greetings from the Other Side)” depicts a woman in a bikini floating down a river in an inner tube, distracting the border guards, making a mockery of the border wall. Clark has quite a few works in the show in his distinctive cartoonish style with satirical wit. “Ridicule is sometimes the best weapon. Sometimes it’s the only weapon,” Clark writes.

The brightly colored foods and their vivid advertisements found at the border are inspiration for “Food Signs,” Victoria Suescum’s series of paintings. There is a mango paleta (ice pop), mango and melon agua frescas, la raspa (snow cone) and coctel de fruta (fruit cocktail). They’re fun emblems of the way food is the universal connector.

Molina and Martinez collaborated on a sculpture made of barbed wire formed into the shape of a rattlesnake. Though the barbed wire suggests boundaries, its meaning is transmuted by making it a snake, Molina said, because like the snake sheds its skin, everything goes through transition and renewal.

Alejandro Macías’ “Citizen” depicts a figure wearing a T-shirt bearing the American flag painted in the green, white and red of the Mexican flag. His body is painted in the striped textile design of the serape blanket.

On his T-shirt is a sticker that says, “I voted.”

What to know if you go to The James Museum

“Icons & Symbols of the Borderland: Art from the U.S.-Mexico Crossroads” is on view through Jan. 19, 2025. There is a vast amount of programming throughout the show’s run, including tours, lectures, a book club, dance performances and workshops and a film screening. There is an artist talk with Oscar Moya on Nov. 8 and a printmaking workshop led by Moya and Lydia Limas on Nov. 9. $10-$23, free for kids 6 and younger. 10 a.m.-5 p.m. daily except Tuesdays, when the hours are 10 a.m.-8 p.m. and admission is $10 for adult and $5 for ages 7-18. 150 Central Ave., St. Petersburg. 727-892-4200. thejamesmuseum.org.