Amid a global movement to return artworks to their countries of origin, about 750 pieces by predominantly Black Brazilian artists are coming home after being exhibited in museums across the United States and Canada.

The sculptures, paintings, prints, religious objects, festival costumes, toys and poetry booklets have been outside Brazil for more than 30 years and are now being donated to a museum in the country’s Blackest state, Bahia.

About 80% of the region’s population is of African descent – compared with a national average at 55% – and Bahia is the centre of Afro-Brazilian culture, with its cuisine, religiosity and art deeply influenced by Yoruba customs.

The works that will be repatriated – called “popular art” as they were created by self-taught artists – left Brazil after a 1992 visit to Bahia’s capital, Salvador, by the US art historian Marion Jackson and artist Barbara Cervenka.

The two women were researching non-European arts when an African American artist friend invited them to join him on a trip to Bahia.

“At first, it felt like a cacophony of things. But as we looked further, we began to distinguish who was creating these pieces and what was happening. We met the artists, came back [to the US], took stuff back with us and came back [to Brazil],” said Cervenka.

Between 1992 and 2012, during their summer holidays as professors at the University of Michigan, they made at least one annual trip to Brazil.

The two friends recount that the artworks were mostly bought – “a little bit through grants, but mostly through our own resources”, said Cervenka – directly from the artists, but some of them were gifts.

Although most of the pieces are by artists from Bahia, there are also those from Pernambuco and Ceará, also in the north-east.

“The real challenge was bringing them [to the US],” said Jackson.

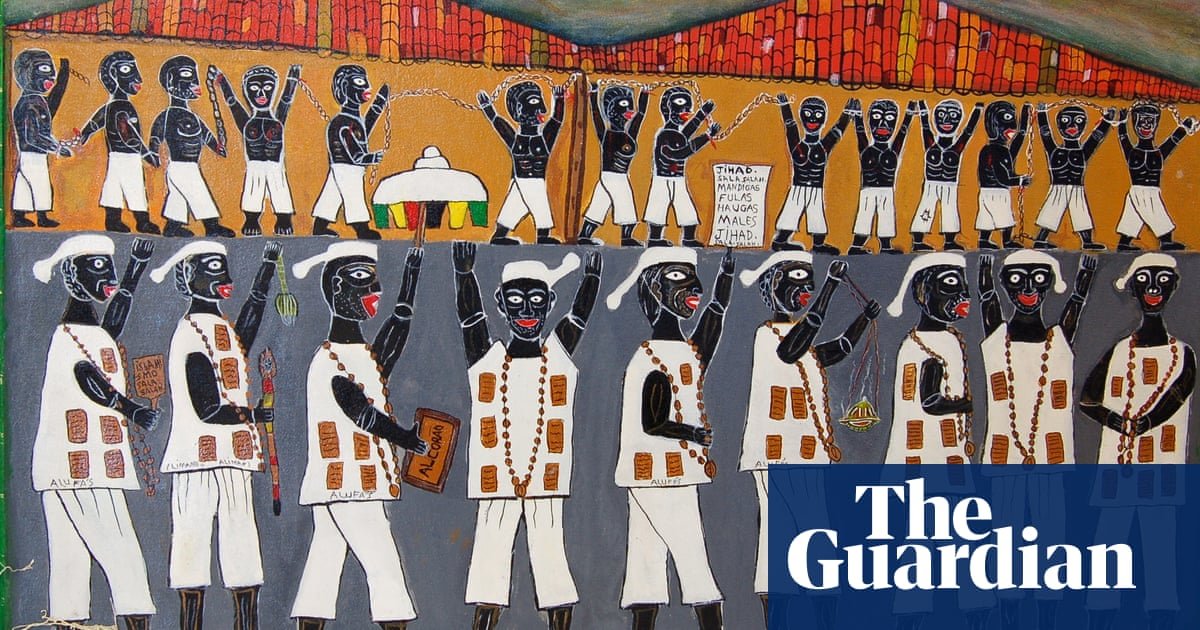

The 750 pieces from nearly 100 artists vary in size, ranging from the painting Procession of the Sisterhood of the Boa Morte, by Lena da Bahia (1941-2015), to a massive wooden sculpture named Oxalá, 7ft tall and as thick as a tree trunk, created by Celestino Gama da Silva, known as Louco Filho (the Madman’s Son), a reference to his father, Boaventura da Silva Filho (1929-1992), who was also an artist and was nicknamed Louco.

To transport that piece, the academics had to send a small truck to Cachoeira, 120km from Salvador, and then purchase several mattresses to wrap the artwork for shipping on the flight.

“We put the collection together initially to open cultural doors between North and South America,” said Jackson.

They established a non-profit organization called Con/Vida to organise the exhibitions. The fact sheet for one of those stated: “How many North Americans know that ten times more Africans were brought in bondage into Brazil than into the United States?”

Approximately 4.86 million enslaved Africans were disembarked in Brazil through the transatlantic slave trade, while the US received 388,000 (according to estimates from the SlaveVoyages database). Even within Brazil, these numbers are not widely known.

This is because the country still struggles to face its history, says Jamile Coelho, one of the directors of the National Museum of Afro-Brazilian Culture (Muncab), which will receive Jackson and Cervenka’s donation.

“Valuing Afro-diasporic artists is a very recent process,” said Coelho, adding: “Even today, Black artists are ignored in art schools.”

Despite being a country with a majority of African descent, Brazil has few museums dedicated exclusively to the memory of the Black population – the largest of which, Afro Brasil, is located in São Paulo.

The Muncab director views the repatriation of 750 pieces as part of a global movement to return items to their countries of origin. However, she sees a crucial difference compared to cases where items were “stolen”, as in “most European museums”.

“That’s not the case for what we’re about to receive. We verified that these were legal purchases,” said the museum director, adding: “Nevertheless, they [Con/Vida] still understood the importance of returning these works to Brazil.”

Discussions are still ongoing about how and when to send the pieces, which are now stored in an office in Detroit. “We hope to do it within the next year,” said Cervenka.

Muncab has stated that once the pieces arrive and are featured in an exhibition in Salvador, the plan is to lend them to other exhibitions across the country.

The conversations began last year when the two also spoke with other institutions. Cervenka explained why they decided to do it now: “As we’ve gotten older [she is 85; Jackson is 83], we realised that we couldn’t continue in the same way with the kind of energy that a project like this needs. So we wanted to ensure that these pieces had a future.”

Their collection also included Peruvian pieces, which were recently donated to the Lima Art Museum, and to the Michigan State University Broad Art Museum.

For Jackson, something fortuitous is the fact that many of the artists are still alive. “So they, their families, and their communities can come and see their work in a museum of real stature. And really being celebrated and recognised as a significant part of Brazilian culture is, I mean, it’s all we could hope for,” she said.