This winter, 22 site-specific light sculptures, projections and immersive installations will illuminate the night skies over Abu Dhabi’s Jubail Island and Souk Al Mina, as well as Al Ain’s Al Qattara and Jimi oases. It’s all part of the second edition of Manar Abu Dhabi, running until January 4 under the theme of The Light Compass. “We crafted the curatorial direction based on traditional culture and knowledge of navigation,” the event’s Artistic Director, Khai Hori, explained to Condé Nast Traveller Middle East this week in Abu Dhabi. “We’re looking at astronomy, the moon and the sun as guiding lights, using tradition, history and heritage as our first guides, and then showing artworks manifested through technology, combining nature and history, referencing knowledge and culture from centuries ago.”

The show juxtaposes natural forms of light with artificial sources. “Here you can touch it, shape it, interact with it,” says Hori. “In the past, light was light. Manar Abu Dhabi reminds people that we can control light in terms of the artworks, but that it’s all inspired by light that we cannot control.”

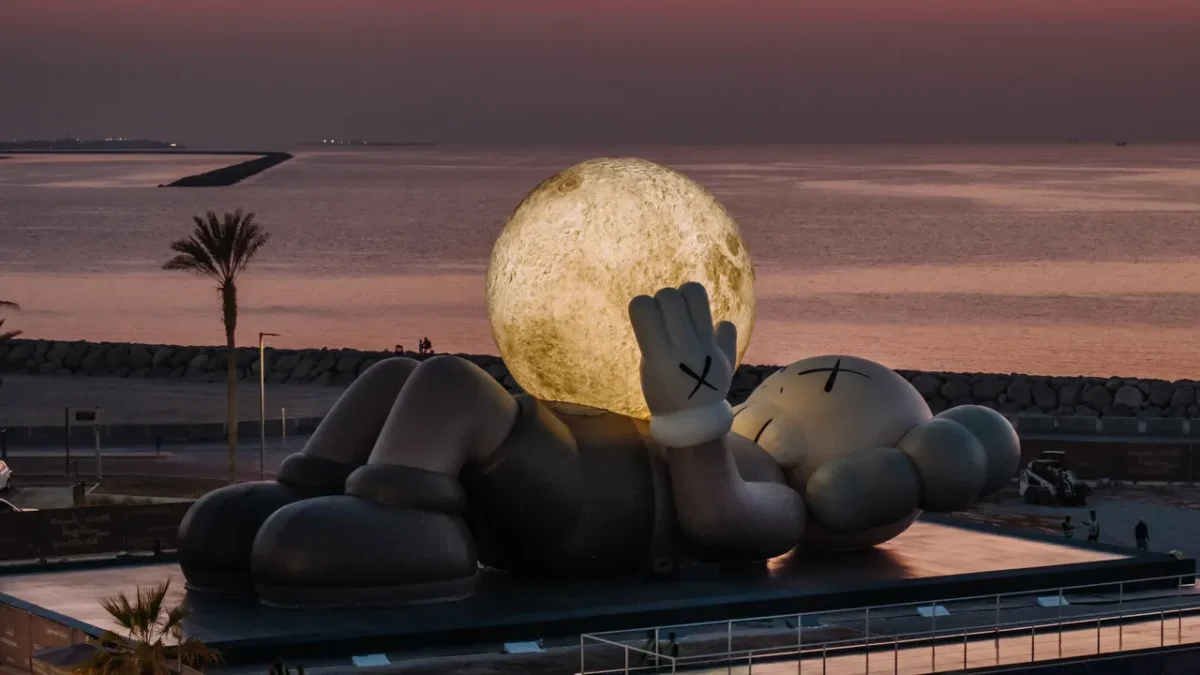

The artworks by fifteen Emirati and international artists from ten countries are spread over spaces that incorporate both natural settings and historical elements. In Al Ain, the works sit next to centuries-old structures and oases. On Jubail Island, they are bookmarked by largely unknown archaeological sites and protected mangroves. And in Souk Al Mina, a monumental work by Kaws sits alongside the port.

While the concept of seafarers and nomads in the Gulf using light and the stars to find their way is central to experiencing Manar, Hori hopes visitors will also navigate their own journeys through the works according to the light that draws them. There are suggested routes, but wandering off the paths is encouraged. “We don’t want the journey to be flat” says Hori. “Some of the works are designed to be more introspective. You walk through them, feel them, touch the light. We don’t want to give all the information away and tell you how to feel. We want you to ask yourself what it is, and what does it bring to you.”

There’s a playful mood to many of the interactive works, and the fact that entry is free avoids the exclusionary feeling that many art experiences can impose on visitors not used to museums and galleries. The site is also accessible to wheelchair-users, with buggies available for those who need them. “As a curator, I like to provide different points of entry to all, whether you’re an art lover, a mother with a child, the child itself, or an influencer who just wants to take a picture,” Hori says. “Whatever your expectations bring, however you want to interact with or see this exhibition, I believe it’s up to you. You don’t need to understand art to see this. You can play with it, meditate on it, let it affect you, but not really understand it until you go home and think about what it was.” Some of the works are pure drama. Others are more understated. Many are designed for interaction and play. When I visit, I’m surrounded by children playing with the sand and touching live plants that form part of some of the works, and by adults playing with interactive touch screens, seeing their faces appear in some of the works.