When viewing paintings, people usually focus on what they can see. But often, the stories behind the painting — from how it was made to how it got to a museum — are just as interesting.

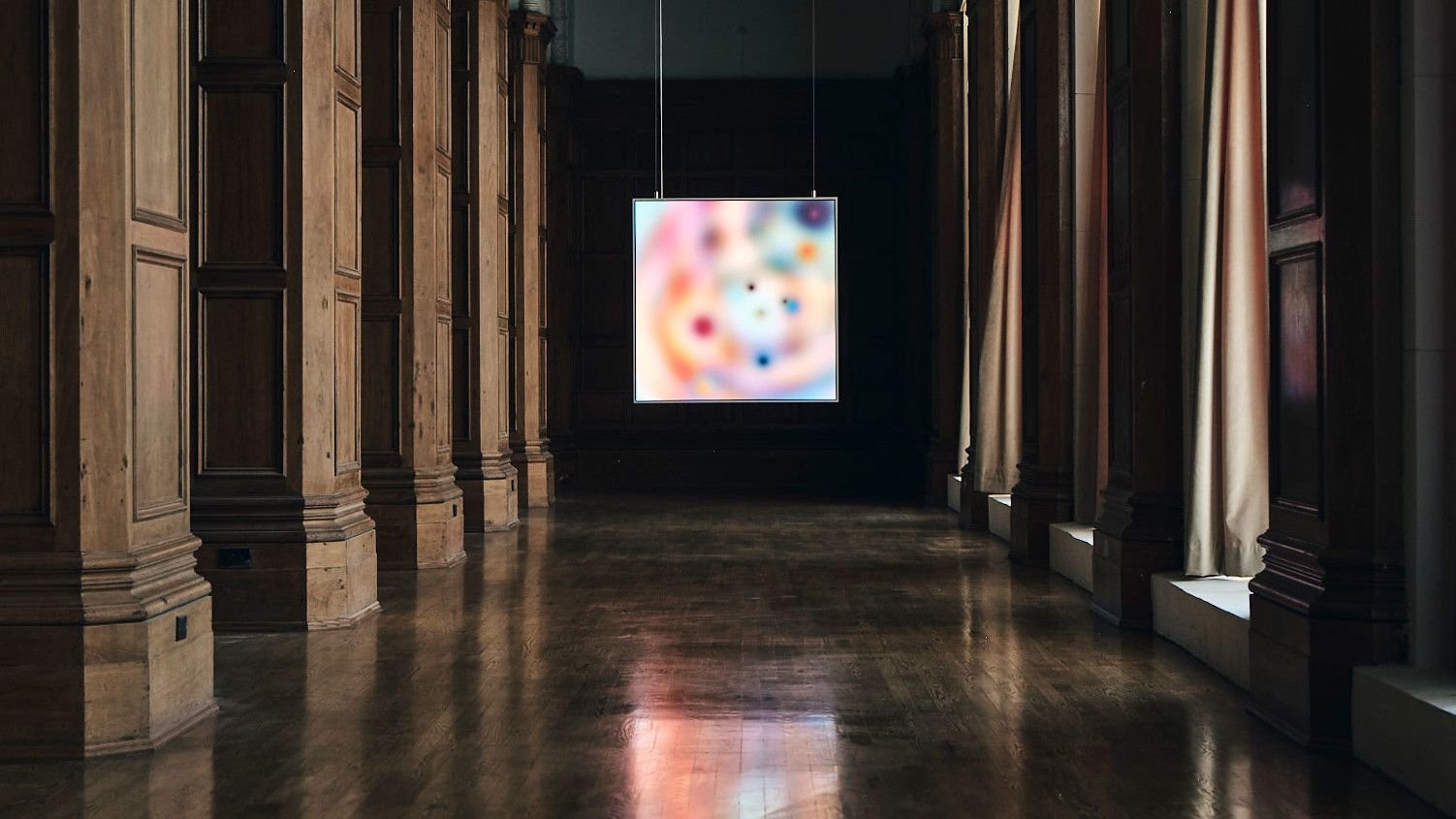

“On the Same Wavelength: Art, Science & Conservation,” a new Nasher exhibition, uses science to peer into the mysterious past of certain artworks. In the process, it highlights an often-overlooked intersection of art and science and provides insights into the history of art.

“On the Same Wavelength: Art, Science & Conservation” resulted from “Curatorial Practicum: Exhibition Development and Design,” a course in the Museum Theory & Practice Concentration of the Art History major. In the course, students worked under the tutelage of Dr. Julia McHugh, Trent A. Carmichael Director of Academic Initiatives and Curator of Art of the Americas, and Associate Curator Dr. Katherine Werwie to design an exhibit. They received assistance from Heidi Kastenholz, James Bonk Fellow and doctoral candidate in chemistry, and scientists and art conservators from Duke and beyond.

The exhibit was co-curated by four Trinity students: juniors Anna Grace Grossnickle and Hailey Kasney and seniors Abigail Hartemink and Beatrice Kleeger. Each was responsible for several items from the Nasher’s extensive collection that had unknown origins or faced unique conservation challenges. Over the course of the semester, they investigated the artworks’ stories using the tools of technical art history, which combines science, art conservation and art history. Each student had the chance to present their findings at the exhibit’s opening Jan. 30.

Anna Grace Grossnickle chose to study a statue of an infant Jesus of Nazareth. She learned about the history of its cleaning and maintenance, and conducted several pigment analyses in hopes of gaining more insights into the piece’s origins. While she didn’t fully uncover the piece’s story, she helped narrow down its origins and discovered that the doll was originally dressed in garments. According to an email to the Chronicle, Grossnickle took the class to confirm her interest in museum work as a career and hoped that visitors would leave curious about how science and conservation can help tell art’s story.

Abigail Hartemink focused on “Allegorical Portrait of a Lady,” a 17th Century Pieter Conelisz van Slingeland portrait. Using infrared reflectography, she saw beneath the layers of paint to discover a sketch underneath. This revealed how the painting was drawn and provided more details about the heavily shaded section on the painting’s left side.

Heidi Kastenholz discussed “Madonna of Humility,” another painting with an uncertain history. Through X-ray fluorescence spectroscopy, she analyzed the art’s elemental composition, revealing the presence of specific compounds that allowed her to identify which paints were used, providing new insights into where and when the painting was made.

In an interview with the Chronicle, Kastenholz said she wants to work in technical art history and has devoted her doctoral work to related subjects. Kastenholz learned about the exhibit from a department email and quickly decided to join as its scientific consultant. The process was both a teaching and learning experience, as she educated curators on different techniques while learning about art terminology and museum work. She was particularly excited to “help people look at art like a scientist would” and appreciated the creative freedom given to student curators, who were allowed to change the wall color to provide a stronger contrast to the artwork.

Hailey Kasney discussed a wood friar the Nasher had long suspected was a reliquary or artifact container. Nearly 60 years ago, that same statue was brought to the Duke hospital and X-rayed to discover what might be inside. The results were inconclusive, which prompted a new scan for this exhibit using a more powerful CT Scan.

The new scan revealed an empty, lined cavity inside the statue, confirming that it was likely a reliquary. According to an interview email, Kasney has wanted to take the course since seeing the work of a previous class, and called seeing her curation in the Nasher “an absolutely surreal feeling.” She wants all visitors to the exhibit to “be curious” and “engage with the interactive components,” leaving with “an appreciation for collaboration.”

Beatrice Kleeger examined a Teotihuacán incense burner. Traditionally, such items were used for ritual purposes and disassembled after the ritual concluded. However, this piece was later reassembled, and she spent part of her semester trying to understand how they accomplished this. Her work provided new insights into the role that modifications play in preserving art.

In addition to the artworks covered in the exhibit’s opening, “On the Same Wavelength: Art, Science & Conservation” showcases a number of other works. These range from statues to large paintings to a work painted specifically to fade slowly over time. Each piece is accompanied by an exploration of the piece’s story and a description of the methods used to study or protect it.

Overall, the exhibit is an enjoyable one. Though limited in number, the pieces offer significant interest, and each has a story worth learning. The exhibit’s overall focus is also intriguing, demonstrating how science can be used to protect art and enhance our appreciation of it, showing that these two distinct fields can still work together. In doing so, the exhibit also makes a strong case that the story behind pieces of art is often just as interesting as the pieces themselves. After all, art doesn’t exist in a vacuum; it is the product of its time and cannot be truly understood without this added context.

On the Same Wavelength:

Art, Science & Conservation will be in the Nasher until June 22, 2025

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Sign up for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.

| Recess Editor

Zev van Zanten is a Trinity junior and recess editor of The Chronicle’s 120th volume.