Both types of memorial contain the names of the fallen, which are either carved into the granite or are picked out in gold on the dark wood.

There are not many memorials which are bona fide works of art, made by a renowned sculptor, which must have looked daringly modern in their day.

The 11th Century St Agatha’s Church at Easby, near Richmond, is renowned for its 13th Century wall paintings – it has some of the most complete examples of medieval wall paintings in the country.

But in one aisle, there is a striking, art deco memorial to a local soldier who was killed during the Battle of the Somme in the First World War.

Next to it is the wooden cross beneath which his body was buried immediately after he died on September 4, 1916.

In contrast to the artistically designed memorial, the cross bears his name crudely stamped onto strips of metal, and at the bottom is a tideline which shows how deeply the wood was pushed into the churned up mud of the Somme battlefield.

This is a commemoration of 2nd Lieutenant Robert Percy Pulleine, known as “Bobbie”, who hadn’t even reached his 20th birthday when his number came up.

He’d been born in Chelsea in 1896, attended the extremely prestigious Wellington College in Berkshire, from which he’d joined the 18th Brigade, Royal Field Artillery.

His family, though, were steeped in North Yorkshire.

His great-grandfather, Robert Pulleine, was the rector of Kirby Wiske, between Northallerton and Thirsk, and his grandfather was Lieutenant-Colonel Henry Burmester Pulleine.

The lieutenant-colonel was born at Spennithorne, near Leyburn, and died, aged 40, in KwaZulu-Natal in southern Africa. He was leading the British forces at the Battle of Isandlwana on January 22, 1879, in the Anglo-Zulu War in South Africa, when, in his tent, a Zulu warrior stabbed him with an assegai spear. Britain’s defeat in the battle was regarded as its worst, and most embarrassing, for 150 years although Pulleine, despite his leading role, escaped much of the blame.

His father erected a memorial – a traditional stone cross – to him in Kirby Wiske churchyard.

The lieutenant-colonel’s son, another Henry, was born at sea in 1867. He survived his military activities, rising to become a captain, and retiring to Sandford House on the edge of Richmond.

To his son, Bobbie, Sandford House was the family’s country home when he wasn’t away at school or in the army.

But Bobbie didn’t last long at the western front, killed two months into the Battle of the Somme when his D Howitzer Battery was itself hit by a shell. The makeshift wooden cross was pushed into the ground, near Albert, where his body was hurriedly buried.

After the war, his body was moved to the Becordel-Becourt cemetery and, unusually, his parents were able to retrieve the cross which they placed in their local church alongside the remarkable art deco plaque.

It was designed by Percy Metcalfe, a sculptor who, like the Pulleines, was a Yorkshireman. He came from Wakefield, attended the Leeds School of Art and did a term at the Royal College of Art in London before enlisting in the Royal Field Artillery – the same regiment as Bobbie.

Indeed, Metcalfe had his leg shattered on the Somme and was invalided out in July 1916 – a month or so before Bobbie’s death.

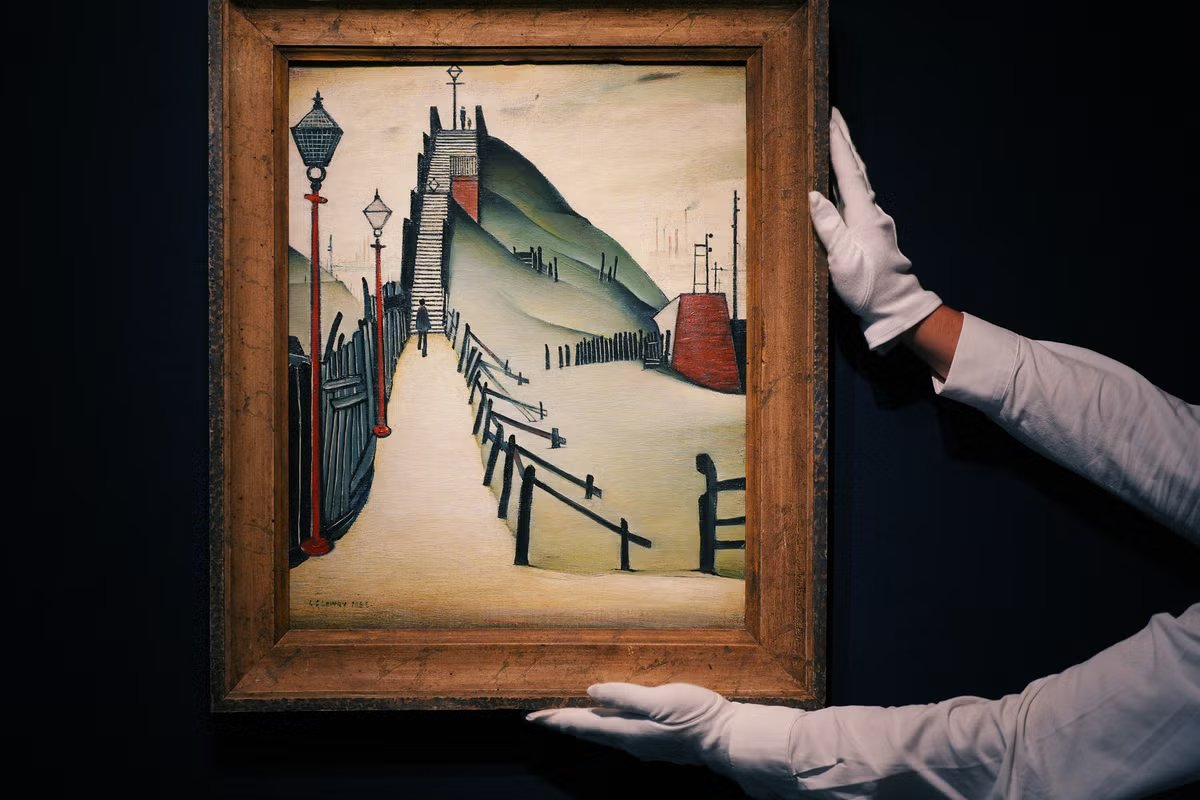

The plaque in Easby church was probably one of Metcalfe’s earliest commissions after the war. Because of his injury, he struggled to stand while sculpting and so, although he did produce large scale pieces, he became renowned for his art deco work for the Royal Mint.

In the same, distinctive style, he designed the 1924 British Empire Exhibition medal and in 1928, he designed the first set of coins for the Republic of Ireland.

His depiction of the Dublin Trinity College harp (which can also be seen on the Guinness label) was so successful that it has become one of Ireland’s national symbols and can still be seen on euro coins.

Metcalfe’s biggest project was designing in 1937 the art deco set of coins for the new reign of King Edward VIII. Edward, though, abdicated before they could be issued.

Metcalfe went onto design the image of King George VI which appeared on the coinage of practically every Commonwealth country and then, in 1940, he redesigned the George Cross.

And, in a small North Yorkshire church, surrounded by the ruins of a 12th Century abbey, can be found his remarkable, stylised and beautiful plaque dedicated to the local soldier who, unlike him, never made it home from the mud of the Somme.