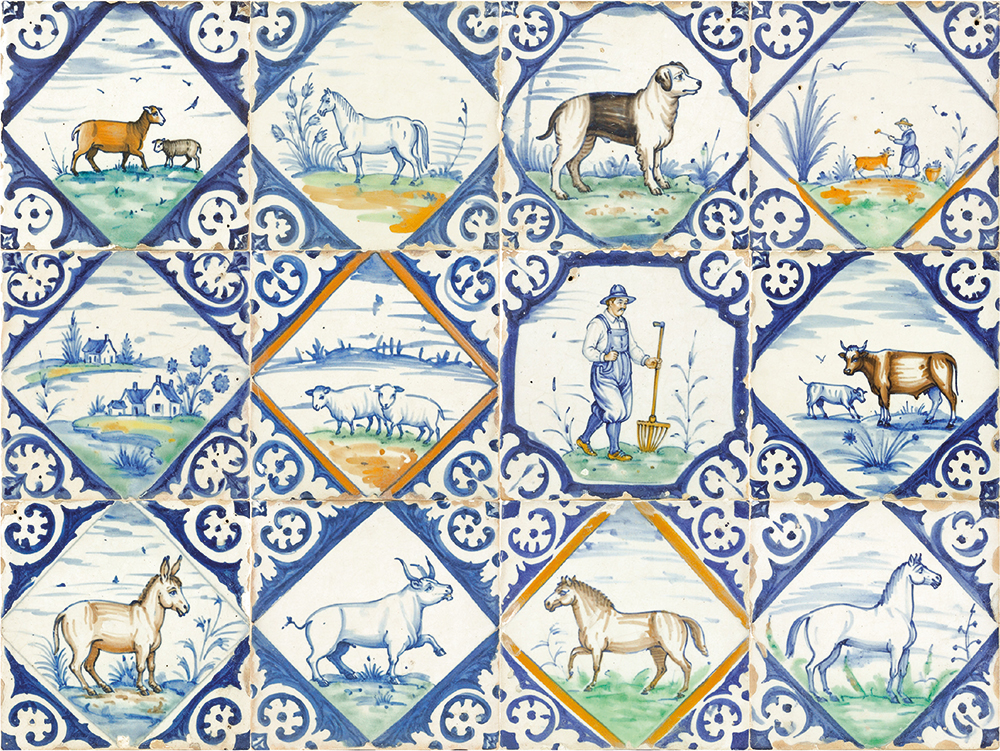

In front of me is what appears to be an authentic Delft tile. The surface of the tile is mottled, and painted on to it is a picture of a man. The blue tones blur and fade into the edges. Delicate brush strokes are visible if you peer closely. It looks as though it were made many years ago. Except it wasn’t. It was designed this morning by artificial intelligence and created in a small factory near Stoke-on-Trent, using some of the most advanced printing technology available.

‘Josiah Wedgwood would have loved what we are doing… I suspect William Morris would have hated it,’ says Adam Davies, the co-founder of the company creating these tiles. Davies, who is currently reading Radical Potter, Tristram Hunt’s biography of Wedgwood, draws inspiration from the renowned ceramicist’s innovative spirit.

In May, Davies and his business partner Jack Marsh, both in their mid-twenties, launched Not Quite Past. Through their website, customers can use AI to create bespoke tiles in the traditional Delftware style. To date, more than 70,000 designs have been generated by a growing and curious audience, with the AI continuously trained to produce new ornaments. A single tile costs £9.99.

The AI has learnt to create mistakes to allow for what looks like human error

The concept came to them during a historical walking tour of Birmingham. ‘We were thinking about ornament and how we once made attractive mass-produced decorations for buildings. Why don’t people do that now, we wondered. Obviously, people could do that now. But in a way, the arrival of AI is a very similar process to what happened in the Industrial Revolution, when it suddenly became much cheaper to make things, so people began to cover their buildings with them.’ They hope that their technology might encourage a revival in mass-market decoration.

And how do they train the AI? ‘We direct it towards Delft tiles from all around the world, and in particular those found in museum collections that are available to view online,’ explains Marsh. ‘We want to bring tradition into AI and help guide the technology to be historically sensitive.’ It is why the tiles look authentic; the AI has learnt how to blur the images to give the appearance that they have been produced by hand. It can create mistakes to allow for what looks like human error.

Marsh, who read history of art at Oxford, clearly sees this new technology as a distinct type of art form. ‘You can play against the grain and introduce other styles into it. I’ve created tiles that take their inspiration from Klimt and Chagall.’ He understands why people might not agree that AI can compete with the work of an artist, but he also sees AI as something that can occupy a parallel space. ‘AI is a challenge to art. Just as photography was, given that it heightens the crisis of representation.’ But he feels artists will respond to this challenge, much like impressionism and modernism were responses to the advent of photography. ‘A lot of people think it’s going to take over; I just think it’s its own field.’

Davies, whose background is in computer science and history, tries to explain how the AI works in layman’s terms. ‘The AI we use is based in the US. It runs on Nvidia chips, which are very expensive. We rent them on ten-second intervals. We then do some transformations behind the scenes to get the image that you select ready for the ceramics.’

Once the image is decided on with the customer, a company called Digital Ceramics in Stoke-on-Trent takes over with the printing process. ‘We could make 10,000 tiles and each one would be unique and beautiful, but also cheap. It would look as though an artisan had painstakingly made each one. But they’re not handcrafted and we’re proud of that,’ says Marsh.

The tiles are certainly beautiful, if a little eerie. Before I visit the factory, I play around with the AI to see what it generates, suggesting prompts based on buildings, people and fruit. What comes out isn’t always an exact representation of the input, more an interpretation. There is something uncanny about what the AI dreams up. But what Marsh and Davies have found is that the limited space and colour palette of the Delft tile has a liberating effect on customers. ‘One of the problems with AI is that it can do anything and therefore people end up doing nothing with it because they are overwhelmed by the options. How do you know what you want to ask it to do? We have limited what we are using the AI for, and that seems to help people decide.’ Marsh describes the Delft tile as a ‘world in blue and white’. ‘There’s a kind of a classical sparseness to it,’ he says, ‘but it’s also very alive and human.’

What do people want on their AI Delftware? ‘Dogs,’ Marsh laughs. ‘The English love dogs. They’ll say, “Oh that’s my dog”, and it’s not, it’s an AI dog, but they are convinced it is their dog.’ Frogs are also proving to be popular, as are more modern subjects. ‘One of our customers is redoing a house in Norfolk. It’s an old medieval house in very bad repair. Some of the antique Delft tiles need replacing. The owner of the house worked in the defence industry and has designed a range of tiles featuring submarines to be included alongside the existing tiles.’ Unsurprisingly, the oldest subject of them all is popular, too. ‘People like to put quite lewd suggestions into the prompt box,’ says Davies. Will the AI comply? ‘No… but we can override certain settings, so if that’s what people really want, we can arrange it for them.’

In fact, they can steer the AI in all sorts of directions, X-rated or otherwise, so they can create more precise designs for customers if the technology isn’t quite playing ball. For customers who still can’t decide, pre-designed tiles are also available on the website. If a customer would like to decorate an entire room in AI Delftware, they will offer significant discounts on the price of the tiles. ‘We’d love to work with someone doing something similar to the wonderful cellars at the Oranienbaum Palace in Germany or the extraordinary Tente Tartare folly of the Château Groussay in France,’ says Marsh.

I find it exciting spending a day with them in the factory. There is plenty written about the somewhat catastrophic effect AI will have on our future; it’s cheering to meet two young men who want to use it to decorate our homes. They both agree that their favourite tiles are the space-themed ones. ‘We like seeing astronauts and rockets done in Delftware. We like the historical mix.’

I also meet Mark Wood, who runs Digital Ceramics. His family have worked in the Staffordshire pottery industry for generations. His father made dinner plates. Wood pivoted into tile printing. The industry had been under threat from cheap mass-produced imports from China, but by focusing on precise, high-resolution small format printing, often using quite traditional lithographic techniques, Digital Ceramics has been able to carve out a new position for itself.

Many of his big clients come from the film and TV industry. The day I visit, laid out in front of the kilns is a floor mosaic commissioned by Nintendo, soon to be shipped to America. Wood shows me some tiles made for the Harry Potter films, including a peach-coloured number with a fruity border which was used in the Dursleys’ suburban kitchen, and a rather attractive moss green tile from the Ministry of Magic.

It was Davies and Marsh who approached Wood with their AI-tile concept. ‘The heritage of Staffordshire pottery is important to us,’ Marsh explains, ‘but we’re really here for the quality of the industry.’ One key advantage of Digital Ceramics is their ability to print with cobalt blue, rather than the standard cyan, lending the tiles an authentic Delft look. Historically, cobalt was imported from Persia; today, much of it comes from Ukraine. Once fired, the tiles are packaged up in the factory and sent to customers – the list of whom is growing.

‘Interior designers are starting to show interest,’ explains Marsh. ‘A well-known American designer has just put in a large order for a house she is working on in the Rockies. The tiles feature lots of ski scenes and dogs.’ Most of the customers so far come from Britain and America, but people from around the world are starting to use their artificial intelligence. ‘We’ve had no orders yet from the Dutch.’ Perhaps they’re not quite ready for the AI revolution.

‘We’ve had no orders yet from the Dutch.’ Perhaps they’re not quite ready for the AI revolution

Remarkably, neither Davies nor Marsh has visited the Netherlands, though their fascination with Delftware is evident. As we talk, we delve into the history of blue-and-white ceramics – a story of cross-cultural exchange. ‘Chinese porcelain influenced Dutch Delftware and British ceramics, while European demand fuelled further innovation in China,’ Marsh explains. In the 17th century, Dutch traders brought Chinese porcelain to Europe, inspiring Delft potters to create their own versions, followed by British ceramicists such as Josiah Spode in the 18th century. In the 19th century, companies such as Wedgwood, Royal Worcester, and Minton made pottery available for the ever-growing middle class.

Though imitation has always been part of the history of blue-and-white ceramics, it would be understandable if traditional studios, such as the Douglas Watson Studio near Henley-on-Thames, might feel anxious about this AI competition. Since 1976, the studio’s artisans have hand-painted Delft-inspired tiles, which cost around £25 each. The current lead time is 24 weeks. By contrast, Not Quite Past offers a far more affordable and accessible option for Delftware enthusiasts.

But Davies and Marsh don’t see themselves as competitors to hand-painted studios. Instead, they see their project further democratising blue-and-white ceramics, which might in turn lead to a new vernacular. ‘There are different markets. There is a market for spending lots of money… we don’t think we’re competitors. It’s very different,’ says Davies. ‘We’re in an age where we have ever greater technology, during a time of unprecedented wealth. And yet a lot of our buildings are very blank. They sometimes feel spiritless. Maybe AI can help by producing decoration that is industrially made but also beautiful,’ says Marsh.

He’s probably right when he says that William Morris would have loathed their radical AI Delftware, but ‘Wedgwood would have absolutely used this technology if he had access to it’.

Design your own AI Delftware tiles at notquitepast.com.