One hundred years ago, at the International Exhibition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts in Paris, visitors to the expo’s China Section would have entered through an archway whose mix of traditional and modern elements kicked off a new craze in architecture — the vestiges of which still dominate Shanghai’s historic neighborhoods today.

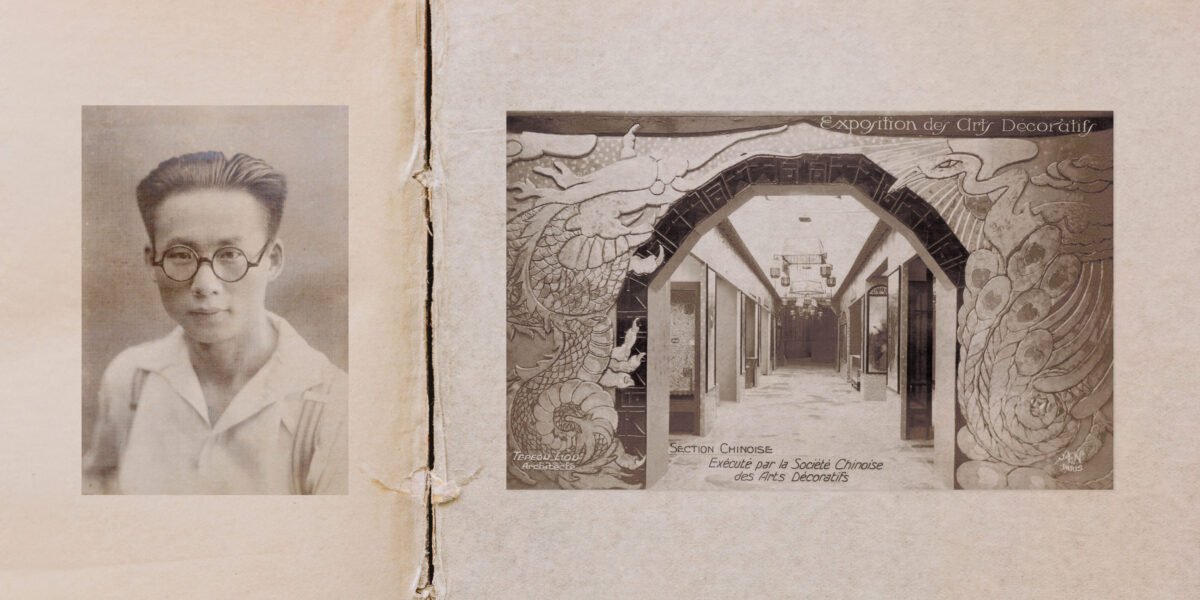

The archway’s design incorporated a “dragon and phoenix facing the sun” motif, a traditional symbol of good fortune, with sharp geometric lines and an avant-garde font spelling the word “Chine.” This experimental fusion of Chinese and Western aesthetics by designer Liu Jipiao (also known as Tepeou Liou), then only 24 years old, would ultimately pave the way for Art Deco’s entrance into the East.

In the 1920s, mechanization and industrial advancements powered huge changes in the European art world. As the curves of the Art Nouveau movement had not yet faded, the hard edges of Cubism, the dynamism of Futurism, and the minimalism of Bauhaus swept in. Mechanical design collided with foreign cultures to create a brand-new design language that incorporated elements from all of these styles — Art Deco. Characterized by bold contours, geometric forms, stepped shapes, and the use of new materials, it emphasized both functionality and decoration, catered to the upper classes, and attempted to align with large-scale machine production.

Around the same time, a group of young Chinese artists were living in Paris, having moved there as part of a wave of Chinese students moving to France after World War I. Many of them studied at or had graduated from the renowned École des Beaux-Arts. Among them was Liu.

He was born in Xingning, in southern China’s Guangdong province, in 1900, and went to Shanghai to study at the China Art University in 1918. The following year, he moved to France. He first studied French, then entered the École des Beaux-Arts in 1922 to study painting, before later transferring to architecture.

He was interested in art with a social function. In 1924, while he was involved in founding the Phoebus Society, which focused on the study of art theory and creation, he also established the Art and Industrial Design Society, which specialized in practical art. At the Exhibition of Ancient and Modern Chinese Art held in Strasbourg that same year, Liu not only exhibited 17 paintings as a member of the Phoebus Society, but also presented practical artworks such as glass vases on behalf of the Art and Industrial Design Society.

In 1925, the French government organized the International Exhibition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts — also known as the Paris Expo — with the aim of showcasing France’s achievements in applied arts, such as architecture, interior design, furniture, and fashion. The organizers required that all exhibited works adopt new design styles, making the expo an arena for modern design explorations — and a landmark event in the development of Art Deco.

The Chinese art world, which saw in modern aesthetics a salve to the country’s woes, was eager to participate. In early 1925, Wang Daizhi, as a representative of the Chinese artists working in France, returned to China to discuss the country’s participation. Cai Yuanpei, then-president of Peking University, even penned an article in the magazine Eastern Miscellany to highlight the importance of the event.

Ultimately, Liu was chosen as the chief designer of the China Section. Besides the archway, with which he expressed his design philosophy of integrating Eastern and Western elements, he was also responsible for the cover of the catalogue for the Chinese Section and glass artworks for display.

In 1927, after eight years in France, Liu moved back to China. Soon after, he was presented with an exciting opportunity to experiment with his design ideals — the 1929 West Lake Exposition in eastern China’s Hangzhou.

As the expo’s chief designer, he led the teachers and students of the Pattern Department of the newly established National Academy of Art (now the China Academy of Art) to depict, through more than 300 drawings, an important moment in the history of modern Chinese design. Their designs included the entrance and interiors of all 13 venues and buildings of the West Lake Expo, as well as a full set of visuals for the Expo including advertising and promotional graphics, tickets, stamps, and badges. They demonstrated the strong characteristics of the localized Art Deco style.

Art Deco found widespread adoption in nearby Shanghai, reshaping the city’s skyline. Sassoon House, which was completed in September 1929, marked the beginning of Shanghai’s architectural transition from a predominantly Western classical style to Art Deco. Subsequent buildings, such as Embankment House and Broadway Mansions, have features typical of American skyscrapers of the same period. Hungarian-Slovak architect László Hudec, a key figure in modern Shanghai architectural design, also began a bold shift toward Art Deco. His Grand Theatre and Park Hotel — two of the more than a thousand Art Deco buildings built in Shanghai in the 1930s — became important symbols of the city’s modernity.

Soon, the Art Deco trend spread out of architecture and into every corner of life in Shanghai. Chinese artists returning from overseas and local avant-garde artists competed to produce new designs and creations, transforming an international style into a Shanghai-style life aesthetic. The sharp geometry, bright metals, and rhythms of machinery found their way into jewelry patterns, furniture designs, and swirling neon lights.

Whether it is the modern women depicted in calendars, with their popular Shanghai-style qipao dresses, or the items found in people’s homes, they all reflected the typical characteristics and local developments of Art Deco. The modern design vocabulary that originated along the Seine River developed into a unique aesthetic by the Huangpu River, and eventually became a brilliant eastern pearl on the global Art Deco map. To this day, Shanghai has more Art Deco buildings than any other city besides New York.

In 1947, Liu fled the turbulence in China and went to the United States, and thereby became separated from his colleagues. However, the Art Deco style he and his fellow artists had championed had already taken root in China, and the buildings he inspired remain historical anchor points to this day.

Translator: David Ball.

(Header image: Left: A photo of Liu Jipiao, circa 1922; right: Liu’s archway design at the Chinese Section of the International Exhibition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts, Paris, 1925. From the Liu Jipiao family archives)