borders, history & landscapes at National Academy of Design

As the National Academy of Design approaches its 200th anniversary, a deeply reflective exhibition titled Past as Prologue: A Historical Acknowledgment, Part I, opened at the Academy’s new space in Chelsea. This exhibition, presented by Chief Curator Sara Reisman and Associate Curator Natalia Viera Salgado, explores the intersections of landscape and territory during the 19th century, inviting viewers to consider how these themes resonate within today’s cultural and political landscape. This first show of a two-part series will be on view until January 11th, 2025.

The artworks on view — from portraiture to landscapes — span nearly two centuries, featuring the Academy’s historical collection alongside contemporary pieces that engage with complex histories of U.S. expansion, colonialism, and shifting ideas of identity and belonging. As Reisman shares in an interview with designboom, Past as Prologue aims to offer ‘a progression in terms of how art was an instrument of nation-building but evolved into an expression of culture…more aligned with contemporary art as we know it.’

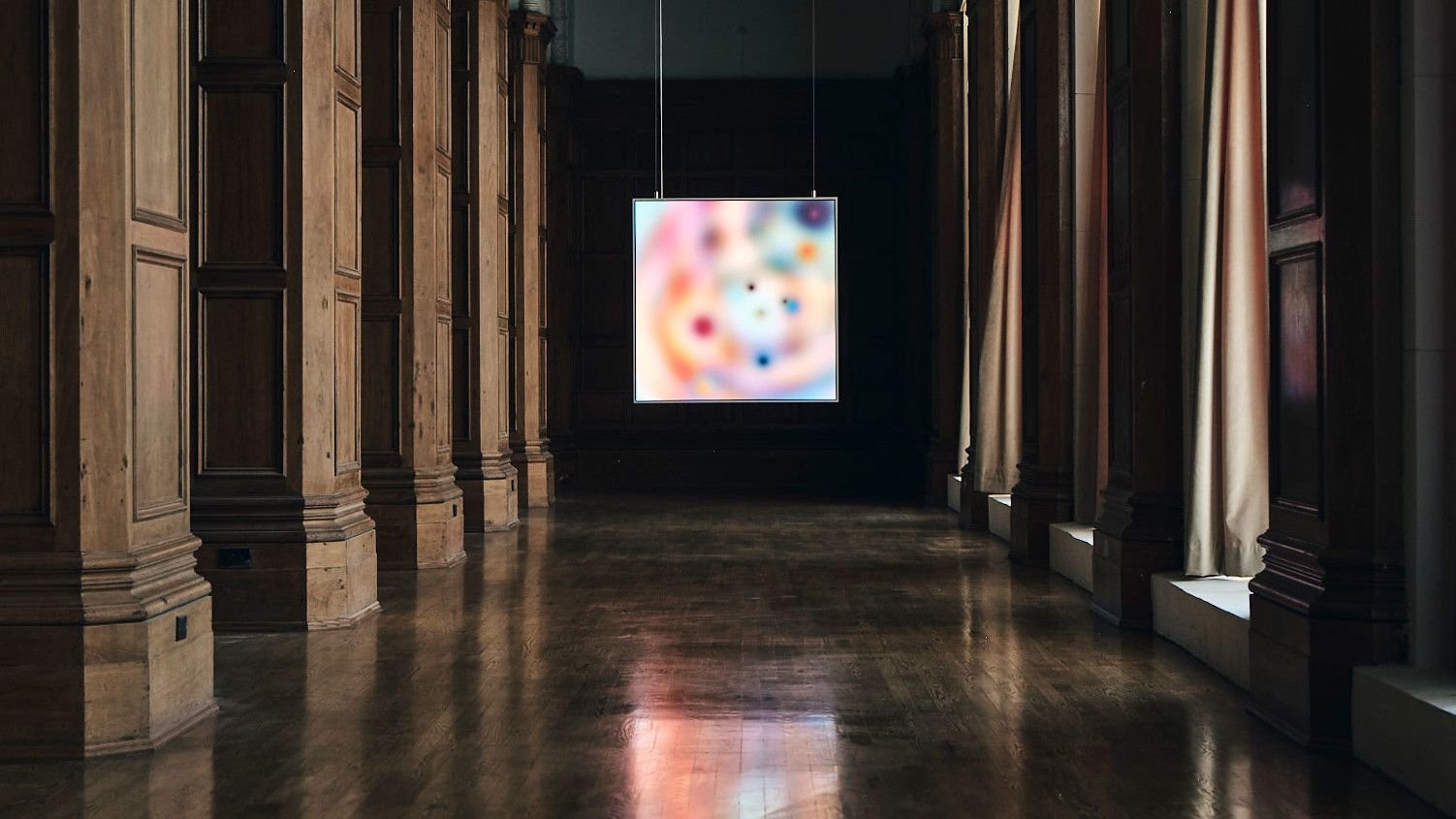

install view, image © Etienne Frossard, courtesy National Academy of Design

past as prologue: Interrogating America’s Past Through Art

With this upcoming exhibition at New York’s National Academy of Design, the co-curators intertwine historical works with modern reinterpretations, sparking dialogues that challenge traditional narratives. For instance, Reisman highlights an early engraving by Moseley Isaac Danforth, The Landing of Columbus, paired with Howardena Pindell’s contemporary piece, Columbus. These works starkly contrast each other, with Danforth’s illustration representing the so-called ‘discovery’ of America, while Pindell’s piece addresses the atrocities of colonization. By displaying these works in dialogue, Reisman demonstrates the trajectory of American art from its role in forming national myths to serving as a medium for critical reflection. ‘This arc of art history and American history,’ Reisman notes, ‘is emblematic of the Academy’s evolution.’

A focus on landscapes, both idyllic and exploited, offers a nuanced portrayal of the American experience. Traditional Hudson River School landscapes are set alongside works by contemporary artists like Sonny Assu, whose interventions on historic landscapes disrupt the myth of manifest destiny. This type of juxtaposition calls into question the environmental impact of U.S. expansion, as well as its cultural repercussions. By engaging viewers with these contrasting visions of the American landscape, Past as Prologue lends a space for critical dialogue around issues of extraction, migration, and Indigenous rights. Read the full interview with Chief Curator Sara Reisman below!

install view, image © Etienne Frossard, courtesy National Academy of Design

dialogue with chief curator Sara Reisman

designboom (DB): Past as Prologue explores significant moments in U.S. history through art. What curatorial strategies did you use to create a dialogue between the historical works and the contemporary pieces in the exhibition?

Sara Reisman (SR): Working alongside associate curator Natalia Viera Salgado, we tried to create a dialogue between the 19th century — which is when, in 1825, the Academy was founded — and more contemporary artistic practice, to give a sense of a progression in terms of how art was an instrument of nation-building but evolved into an expression of culture in a way that is more aligned with contemporary art as we know it. The two groups of work where this national identity becomes most apparent is in portraits and landscape.

A few key examples are an engraving of a landscape — or really seascape — of The Landing of Columbus by Moseley Isaac Danforth from the mid-19th century. This tiny work is an illustration of the victorious explorers’ ‘discovery’ of the new world. It’s installed across the gallery from Howardena Pindell’s Columbus, 2020, which is a maximally scaled black canvas, layered with cut outs of hands, black hands layered on a black background, with a pile of black silicon hands on the floor, and above text detailing the atrocities of colonization, including the Spanish explorers gruesome abuses of the native people they encountered. Both of these artists — Danforth and Pindell — were elected by their peers into the Academy. Danforth in 1826 and Pindell in 2009. The two artists are one example in the show of this arc of art history and American history too.

install view, image © Etienne Frossard, courtesy National Academy of Design

DB: In Part I, you highlight themes of landscape and territory during U.S. expansion. How do the works in this section challenge or complicate traditional representations of ‘manifest destiny’ and the formation of the United States?

SR: I think this is partially addressed in the example of the dialogue between works by Danforth and Pindell. Maybe a more direct critique of land and landscape comes through bringing paintings by Hudson River painters like Frederic Edwin Church and Louis Remy Mignot into dialogue with artworks by contemporary artists like Sonny Assu and Enrique Chagoya who are working with landscape but in a more conceptual sense. The Hudson River School painters generally depicted the landscapes as relatively uninhabited save for a figure, or none at all.

install view, image © Etienne Frossard, courtesy National Academy of Design

SR continued: Both Assu and Chagoya intervene on historical paintings of early American landscape by adding cultural references into the image that disrupt the myth of manifest destiny. Assu’s work Home Coming, (2014) is based on the late Irish-Canadian artist Paul Kane’s 19th century painting Scene Near Walla Walla (1848-52) which depicts a group of indigenous people in the landscape to which Assu added an abstract indigenous form floating in the sky. I see this as a form of indigenous futurism, imagining the landscape that doesn’t conform to imperial sensibilities. Chagoya’s Detention at the Border of Language (2019) is a reinterpretation or remaking of German-American artist Karl Wimar’s The Abduction of Daniel Boone’s Daughter by the Indians (1853). Using Wimar’s narrative as a starting point, Chagoya conflates 19th century racist cultural fantasies about the savage Native with the politics of the U.S. border in the 21st century.

install view, image © Etienne Frossard, courtesy National Academy of Design

DB: The exhibition includes both idyllic depictions of nature and works that address the impact of extraction and exploitation. How do these contrasting portrayals of the American landscape contribute to the broader narrative you are constructing?

SR: Two of the works that take up extraction and exploitation in unexpected ways include Mary Miss’ Connect the Dots (2007) and Hock E Aye Vi Edgar Heap of Birds’ Renew For Every One Dance Water (c. 2018). Mary Miss’ work is an installation of blue dots around the gallery that helps visitors to envision the scale of rising water levels due to climate change in a way that is minimalist yet immersive. Heap of Birds’ monoprint is a text based piece that reflects on the importance of and respect for water that are upheld by Indigenous communities across the United States.

These two artists have long held practices that relate to landscape, drawing from different traditions that intersect in their projects that have materialized as earth works. Both of their works on view are imbued with activist sensibilities, Heap of Birds using text and Miss using a simple formal intervention. Together they move away from landscape art as a literal representation, to offer boldly conceptual expressions about the landscape, and in each of their cases, water as landscape.