American architecture’s bright, shining light of the Kennedy era, Paul Rudolph was scrounging for commissions less than a decade later. He may now be best remembered — to the extent his name rings bells — for the heroic, bush-hammered concrete Camelot he designed during the early 1960s to house the architecture school at Yale.

When it opened, it prompted rapturous reviews akin to what, many years later, greeted Frank Gehry’s Guggenheim Bilbao. But the building soon became a piñata for everything wrong with modern architecture.

And Rudolph, who died at 78 in 1997, dropped down the memory chute.

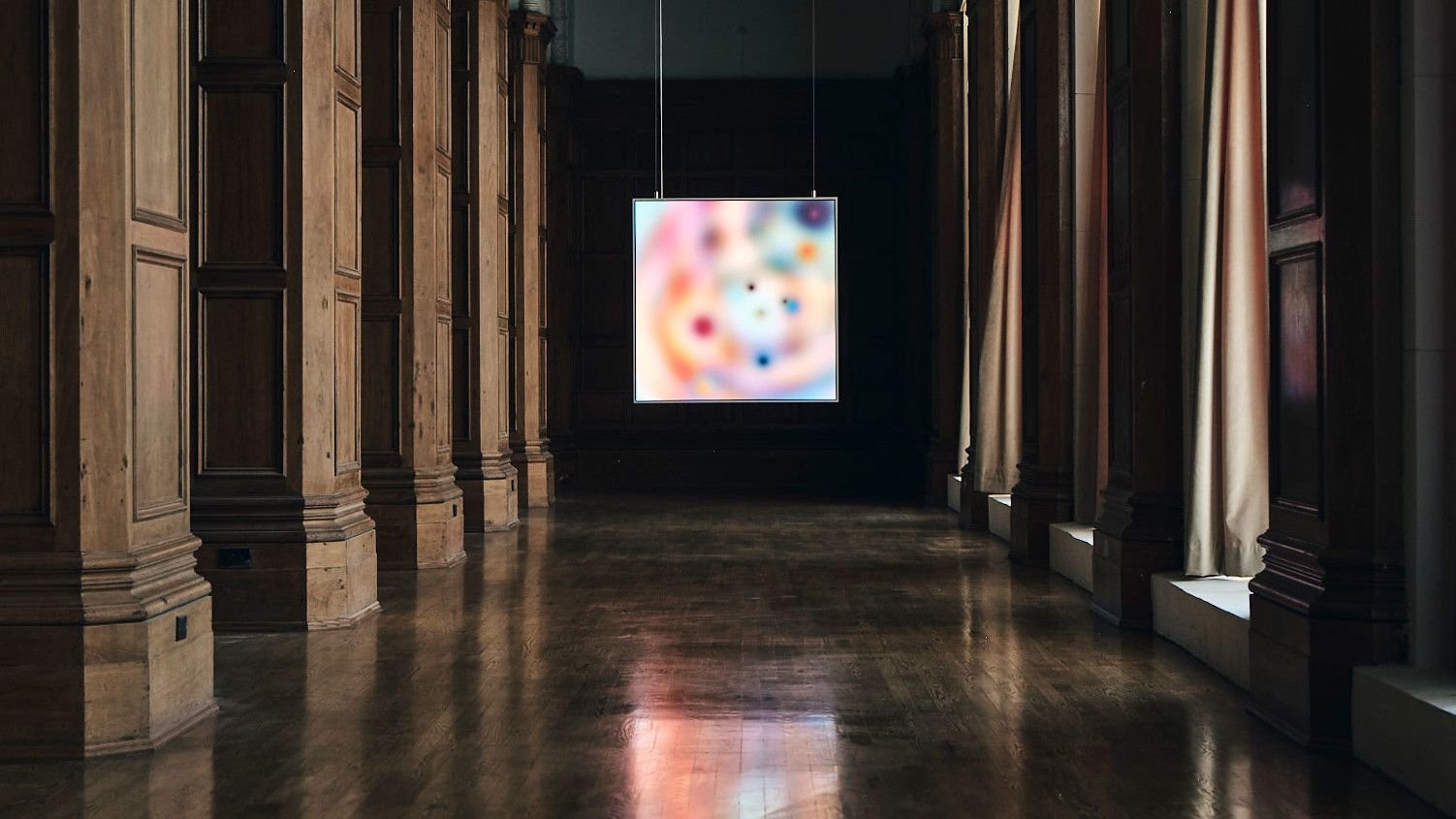

He’s now the subject of a modest but riveting retrospective at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in Manhattan, organized by Abraham Thomas, called “Materialized Space: The Architecture of Paul Rudolph,” whose first order of business is obviously to answer a question people outside architecture circles will ask, namely:

Who was he?

He was the jet age version of Ayn Rand’s Howard Roark. An epic bundle of contradictions, he cooked up phenomenal, visionary drawings and flamboyant, muscular buildings for occupants he made miserable by caring too little about how the buildings actually functioned.

He scolded other architects for being insensitive to context, and perhaps his most uplifting work is a nondenominational brick chapel for Tuskegee University, the historically Black college in Alabama, whose layout pays homage to African-American churches.