On a bright summer morning, the Irish-born artist Sean Scully interrupted a small watercolor for a conversation at his sunlit London atelier. The half-finished abstract rested on a trestle table among paint tubes and empty hummus tubs that they had been squeezed into.

Leaning against the walls were large new oils featuring colorful grids and stripes. Though abstract, they somehow evoked the rich scenery of North Africa; one was titled “Fez,” after Morocco’s second city.

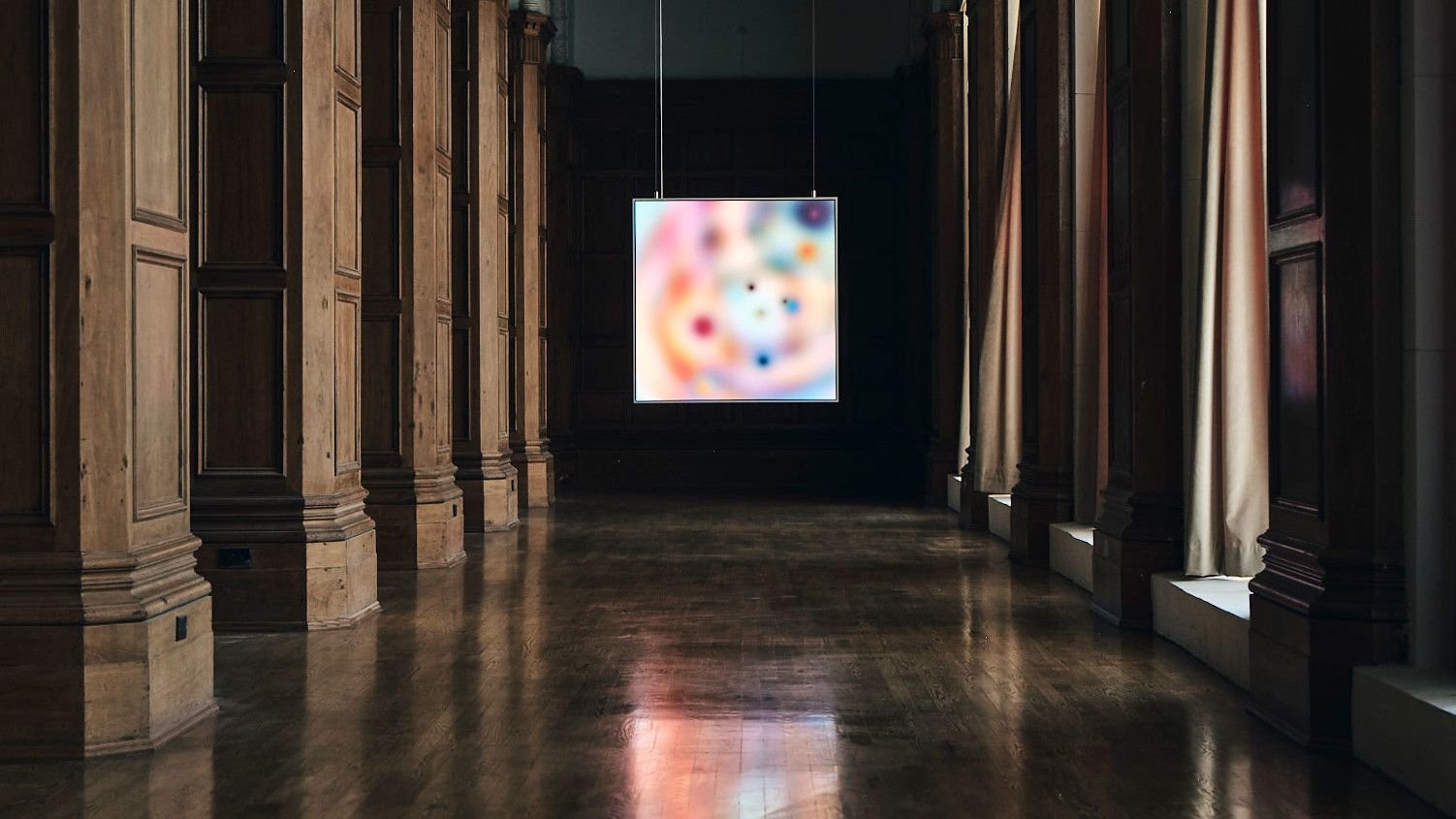

Scully is showing several new paintings at the Thaddaeus Ropac gallery in Seoul as part of “Soul,” an exhibition that is to open on Tuesday, just before Frieze Seoul kicks off. And starting Oct. 29, Lisson Gallery in New York will present paintings he made in New York in the early 1980s.

Scully was born in Ireland in 1945 and moved to London when he was 4, settling with his family in a slum. “It was absolutely dire,” he recalled that morning, in an interview at his studio.

The family soon moved in with young Sean’s loving and incredibly resourceful grandmother; he attended a Catholic school with strict but caring nuns. But when the family bought a house in south London, the little boy suddenly found himself in a vicious environment. “There was nothing except fighting, stealing cars, being in a gang and hoping not to get smashed up too often,” he said.

Young Sean became “the baddest boy in the school.”

“I disobeyed the law,” he said. “I walked on the wrong side going up the stairs and banging people.”

To an extent, that pugilistic side is still there, Scully acknowledged. “Our childhood selves remain,” he said. “I won’t bend the knee for anyone.”

In his teens, he became an apprentice in a printing workshop then a graphic design studio, discovered art, and never looked back. He attended art school in Croydon, in south London, embracing the experience “like somebody who had a religious calling,” then went to Newcastle University. While still a student at Newcastle, he drove a van down to Morocco — wanting to see what Matisse saw — and was entranced for life.

The following conversation has been edited and condensed.

Why did Morocco make such a big impression?

I liked the people. I liked the exotic patterns, the tents on the beach, the stripes all going in different ways.

In Morocco, everything was without borders. There were no boxes containing activity: Everything was all over the place. Carpets were on the wall and on the floor. Tiles were on the wall and on the floor. They were inside, they were outside. People wore djellabas and walked around looking like the walls. It was the geometry of ecstasy.

Not long after your trip to Morocco, you embraced abstraction. Can you talk about that?

First of all, we have to recognize that 50 percent of the world makes abstraction. So it’s not peculiar, and it’s been around for a very long time. I’m part of that, in a certain way. However, I combine it with the pathos of Western painting.

In my work, you have associations with the horizon, with blood, with earth, with gray mist, with the sky in the morning and the sky at night, and then this very somber black bar, which is about finality.

I want a feeling in the painting, so it’s borderline religious. I want everybody in the world to be able to feel that comfort or that love.

You’ve said that American abstract artists can’t achieve this effect. Why not?

Ellsworth Kelly, Robert Ryman and Barnett Newman can’t paint like this, because they’re not European. They didn’t live the life that I lived. They didn’t come from Ireland. All of that is in the painting.

A painting has to be like a person. It has to have a personality and a character and a love and structure in it, a kind of ethical quality. I allow my paintings to be associational and metaphorical.

You left London for New York in 1975. How was that?

People said to me at the time: “Manhattan will kill you,” and I said, “That’s OK, because I’ve already been killed.” When you’re Irish, the metaphor is, you’ve got a boot on your head for 800 years.

New York was like a Cormac McCarthy novel: unbelievably brutal. I had to fix up my loft on 18th Street myself, learn how to do everything. I did construction work, carried sheets of Sheetrock up the stairs.

I stayed because I felt that I had been somewhat slighted in London, and I’m not the right person for that.

In New York, I met people who were unbelievably loyal to me, who gave me a kind of love that was visceral, which I’d never had before.

You’re now based in London, but you’re in New York a lot. Are you moving back to New York at some point?

I’ll never leave New York. I love New York, and I owe it everything.

Given a choice between back-stabbing and front-stabbing, I prefer the latter, and front-stabbing is what you get in New York. If somebody wants to smash you up, they want the authorship, they want the credit. Whereas in London, it’s death by a thousand cuts. So New York suits me.

You lost a son in a tragic car accident in 1983, and often speak about grief. You disagree with people who say that time is the great healer.

They’re all liars. They’re just saying things to escape the dreadfulness of it.

You maybe find ways of putting grief into different activities, compensating for it by saving somebody else. But it’s not honorable to get over it. The person has to live in you. You’re what keeps that person alive. If you get over it, they’re abandoned. Their spirit is abandoned by you. So in a way, I don’t want to get over it.

Are you in a place of contentment now, or, like so many artists, in a state of permanent interrogation and anguish?

I’m very confident about what I am in the art world. I’m very aware of my position. But the things in me that caused me to make art will be in me for 500 years. The furnace in me rages. It doesn’t even need anything to be thrown into it.